On Brian Eno — a Reply to Ian Penman

Brian Eno has written a book!

Well maybe not a book exactly — not a book as we formerly understood it, a cohesive text on a single subject to be read over the course of a few evenings in front of the fire. More of a talismanic object — a “book.” Ready to take its place on the front table of the bookstore alongside Rubin’s The Creative Act, Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish, Byrne’s How Music Works; talismanic objects which need not be read, but purchased, and which promise, through that purchase, to reassure the purchaser that they are still, despite everything, creative.

Eno’s entry — What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory — is especially comforting in this regard, as it reassures the reader that pretty much everything humans do, from posting selfies to cooking meals, is actually Art. Everything, perhaps, except online shopping. We will return to this.

Ian Penman, in a characteristically delightful and nuanced review, mostly ignores the book, instead taking the opportunity to celebrate Eno’s greatness, and to mourn his decline, over the last half century. It is an elegy for a certain kind of genius, and for the world into which Eno, Penman, and I myself were born. But after reading it, I could not shake the feeling that it was unfair to Eno, and overly fair to the world.

I am probably of an age with Penman, and, like him, Eno is one of my last surviving heroes. Penman only really rates his earliest work. He already considers 1977’s Before and After Science to be “insipid.” Myself I would place Eno’s descent into irrelevance somewhat later; I was young enough to cry myself to sleep, suffering my first heartbreak, listening to Ambient 4: On Land, and it is only a couple years after that, with the release of Apollo, that I began to lose interest.

Be that as it may, these are subjective aesthetic judgments; Penman’s first moral critique concerns the 1981 collaboration with David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Penman doesn’t like the music on this record; I happen to disagree. My wife and I relistened to it last week and it’s amazing; as we remarked to one another, it’s not even correct to call it ahead of its time, because there’s really not been anything like its scritchy, looping, layered, polyrhythmic jerking trance funk since.

Penman takes issue with the record’s use of “samples” — which is, first of all, an anachronism. The samplers available in 1981 could only hold 128 kb of memory, nowhere near enough for the extended vocal collages of “Jezebel Spirit” and “Moonlight in Glory”; and in any case no such device was used. The “found” vocals are added the old way, with magnetic tape.

Be that as it may, these are subjective aesthetic judgments; Penman’s first moral critique concerns the 1981 collaboration with David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Penman doesn’t like the music on this record; I happen to disagree. My wife and I relistened to it last week and it’s amazing; as we remarked to one another, it’s not even correct to call it ahead of its time, because there’s really not been anything like its scritchy, looping, layered, polyrhythmic jerking trance funk since.

Penman takes issue with the record’s use of “samples” — which is, first of all, an anachronism. The samplers available in 1981 could only hold 128 kb of memory, nowhere near enough for the extended vocal collages of “Jezebel Spirit” and “Moonlight in Glory”; and in any case no such device was used. The “found” vocals are added the old way, with magnetic tape.

Method aside, what Penman wants to take Eno and Byrne to task for is exoticising, appropriating, taking credit for the creativity of others. This is I think a little ungenerous. There are, to be sure, fraught questions raised by sampling technology; but they can hardly be laid at the door of Brian Eno and David Byrne1. They may have built a song around a recording of Lebanese singer Dunya Yusin without credit, which was admittedly not cool; but to do so they had to physically stop and start a tape deck, cut and splice, lean on the flanges to change the speed, all the lost art of analog recording, and this in an era before the ubiquity of sampling made music licensing an entire field of corporate law.

And that is my fundamental contribution to the lament. What has changed is not Brian Eno, polymath, curious tinkerer with new technology; it is the technologies available for tinkering, and the culture they have created in their wake. Penman reserves most of his ire for Eno’s “generative” works — “software to systematize (and cage, and kill) playfulness.” I don’t disagree. It is hard to care about a series of 10,000 “paintings” produced on screens by a few lines of pseudorandom code — effectively, as Penman points out, a screensaver. But I think it’s worth investigating. How is the notion of “generative art” different now, in the era of the algorithm, than it once was — when Eno (and Penman and I) first became interested in it?

I attended a panel discussion with Eno — I think at the Exploratorium in San Francisco in 1999 or so, though I’m not sure now, the years have blunted my memory somewhat — where he said something that stayed with me ever since. He was describing his then current collaborative project, developing software to generate sound; and how he turned to his collaborator, I forget who it was, after working with the code for hours, and said, “Want to take a break? And just make some … muh … muh …” And, Eno said, they had both been working on the code for so long that neither one of them could even quite say the word, “music.”

At the time, it seemed to me that Eno was recognizing he had gone a little way down a path which was going to become a cul-de-sac. In the event, he did not turn back.

Generative Music

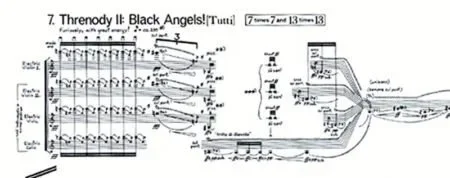

“Generative Music” is a tradition of Modernist (and Postmodernist) composition, composers who wanted to wrest final control over the music from their own hands, to divest, to liberate. Charles Ives left sections of compositions up to the players, marking the score “ad libitum”; Lamonte Young made an early Fluxus work the entire text of which is “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It.” George Crumb’s and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s graphic scores, the interpretation of which was left up to the players, would find a place in this genealogy, as would, certainly, John Cage’s “aleatoric” compositions.

Cage used a couple of different strategies, wishing to be surprised by the music he composed; most painstaking were several compositions in which he determined successive notes by throwing the I Ching. And Steve Reich’s “phasing music” has a place here too; “Come Out,” 16 tape loops of a Black radical saying, “I had to, let some of the bruise blood come out to show them” going out of phase with one another over the course of an incredibly psychedelic 20 minutes was a big influence on the young Eno2. Reich’s other early works, like “Clapping Music,” are also “generative” in the strict sense: Simple rhythmic or musical patterns are allowed to drift in and out of phase with one another according to (also simple) predetermined rules, resulting in music that would be very, very complicated to notate in the traditional manner.

This is work which emphasizes the “process” of composition, and in the analog era these were physical processes that took the time they took. Cage methodically throwing 3 coins, building up a hexagram, over and over again, note after note; Reich cutting the tape, splicing the loops, pressing play on 16 decks and watching it unroll.

How different in the digital era. Cage’s entire discography could be produced with a few lines of code and the push of a button; Reich’s experiments similarly. It would be comical to call such works “process” compositions, were they made today, with the tools available. “Generative” — okay. They’re undeniably “generative.” But what has been lost in the transition from “process” to “generative?”

Penman observes that Eno was influenced by his older friend, the painter Tom Philips. Philips’ masterwork is the book A Humument. To make this work, Philips set himself a simple limitation: He would buy the first used book he could find for threepence, and paint over it. The book he found, a Victorian novel called A Human Document, had wide rivers of type, and Philips spent the next 50 years painting elaborate miniatures over every page, leaving unpainted words and parts of words that reveal a new story buried within the original text. As the work progressed, Philips decided, or discovered, that the protagonist was named Bill Toge; and so a new rule emerged: Every time he encountered words like “together” or “altogether,” these became appearances of the hero.

This is work which emphasizes the “process” of composition, and in the analog era these were physical processes that took the time they took. Cage methodically throwing 3 coins, building up a hexagram, over and over again, note after note; Reich cutting the tape, splicing the loops, pressing play on 16 decks and watching it unroll.

How different in the digital era. Cage’s entire discography could be produced with a few lines of code and the push of a button; Reich’s experiments similarly. It would be comical to call such works “process” compositions, were they made today, with the tools available. “Generative” — okay. They’re undeniably “generative.” But what has been lost in the transition from “process” to “generative?”

The whole book is this beautiful

How would you do something like this in the digital era? Is it possible?

And if it’s possible, is it interesting? Write a few lines of code and press a button?

Penman doesn’t discuss Oblique Strategies, one of Eno’s most enduring productions: A box of 55 cards with gnomic suggestions for overcoming creative obstacles, composed with painter Peter Schmidt [A mutual friend of Eno and Philips, who did paintings based on the I Ching hexagrams — it all falls into place]. Here we encounter maybe the most stark example. Over the years, several people have decided, out of a desire to democratize access to this (extremely useful and beautiful) work, normally available only in limited printed editions, to make an app: You guessed it, a few lines of Javascript, pseudorandomly shuffling Eno and Schmidt’s inspiring phrases.

How would you do something like this in the digital era? Is it possible?

And if it’s possible, is it interesting? Write a few lines of code and press a button?

Penman doesn’t discuss Oblique Strategies, one of Eno’s most enduring productions: A box of 55 cards with gnomic suggestions for overcoming creative obstacles, composed with painter Peter Schmidt3. Here we encounter maybe the most stark example. Over the years, several people have decided, out of a desire to democratize access to this (extremely useful and beautiful) work, normally available only in limited printed editions, to make an app: You guessed it, a few lines of Javascript, pseudorandomly shuffling Eno and Schmidt’s inspiring phrases.

Something has been gained — accessibility. Something has been lost — perhaps not much, but something nevertheless. The process. The process of stopping, shuffling, picking a card, has been reduced to a deterministic algorithm, and hidden, like all algorithms, out of sight of the user.

Something has been gained — accessibility. Something has been lost — perhaps not much, but something nevertheless. The process. The process of stopping, shuffling, picking a card, has been reduced to a deterministic algorithm, and hidden, like all algorithms, out of sight of the user.

The Random and the Pseudorandom

I have, personally, always loved watching physical processes unfold. Raindrops running down the windshield, candle wax dripping on a wine bottle. Grains of sand landing in a pile. I don’t think I am alone in this. However, it is not just the unfolding of a process that delights me. It is the element of surprise, the “aleatory,” as Cage would say. There is, actually, nothing particularly delightful about observing a purely deterministic process play out: A screensaver, say. The date and time, in Helvetica, drift across the screen, “bouncing” (according to predetermined rules) when they reach the screen’s edge. I have whiled away some minutes of my life watching processes like these, and they are minutes I will never get back, and it’s a damn shame.

Watching (or listening to) an aleatoric process, the outcome of which is rigorously uncertain, my mind wanders, in a kind of trance, and new, surprising ideas occur. I am musing, woolgathering. Watching a screensaver at the doctor’s office, my mind is forced into a rutted road to nowhere. I am nowhere surprised by what occurs to me. It is only an endless rehearsal of the known; something to look at while I wait for anything else to happen.

John Cage threw the I Ching, over and over, for hours a day, and added the notes it determined to a physical pad of ledger paper. I could, right now, code an I Ching composition bot to produce an entire symphony — or indeed 10,000 symphonies. I could say the program is the work of art, and these few lines of code contain 10,000 I Ching symphonies! A “generative” work, much as LaMonte Young’s single sentence, “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It,” “generated” the first Velvet Underground record (via his student John Cale), which generated a band for every copy sold.

I jest — but let us ask, what really is the difference between these two ways of composing John Cage’s works?

Most obviously, I do think the absence of physicality in the composition process matters. It is irreducibly less interesting to abstract a process into an algorithm and realize it digitally than to physically perform it. And intertwined with this, the obscuration of the process matters. Cage got to follow along, one note at a time, as his works were composed, and we, listening, experience the delight of surprise, imagining his surprised delight. There is no comparable image, to help me focus my attention, in a work produced by the black box of an algorithm.

These differences are surely important, but there is a deeper underlying difference. Rigorous unpredictability only exists in the physical world.

Several times in this article I have used the word “pseudorandom,” and I am using it with intention. There is no randomness in a digital system. Computers are rigidly deterministic — that is their power. A computer program run 1000 times will give the same result 1000 times. It cannot make mistakes, and that is why computers are valuable.

So, in order to actually write the code for our imaginary digital John Cage, we would need to replace the act of tossing a coin (which is already a simplification of the traditional method of sorting yarrow stalks into piles, and actually has a slightly different probability distribution). We would use a built-in “random” number generator packaged with our programming language. Under the hood, it would work by taking a number from the computer’s state, such as the last few digits of the current time measured in milliseconds, and run it through an algorithm, such as the Mersenne Twister algorithm, to generate more digits from that “seed.”

There is nothing random about this procedure however. Milliseconds tick by one at a time in a completely predictable fashion; the output of a Mersenne Twister is invariable. Anyone with access to the logs of our computer could reproduce the exact sequence of digits we used to compose every note of our imaginary 10,000 John Cage symphonies, and they will be the same, note for note.

The Random and the Pseudorandom

I have, personally, always loved watching physical processes unfold. Raindrops running down the windshield, candle wax dripping on a wine bottle. Grains of sand landing in a pile. I don’t think I am alone in this. However, it is not just the unfolding of a process that delights me. It is the element of surprise, the “aleatory,” as Cage would say. There is, actually, nothing particularly delightful about observing a purely deterministic process play out: A screensaver, say. The date and time, in Helvetica, drift across the screen, “bouncing” (according to predetermined rules) when they reach the screen’s edge. I have whiled away some minutes of my life watching processes like these, and they are minutes I will never get back, and it’s a damn shame.

Watching (or listening to) an aleatoric process, the outcome of which is rigorously uncertain, my mind wanders, in a kind of trance, and new, surprising ideas occur. I am musing, woolgathering. Watching a screensaver at the doctor’s office, my mind is forced into a rutted road to nowhere. I am nowhere surprised by what occurs to me. It is only an endless rehearsal of the known; something to look at while I wait for anything else to happen. John Cage threw the I Ching, over and over, for hours a day, and added the notes it determined to a physical pad of ledger paper. I could, right now, code an I Ching composition bot to produce an entire symphony — or indeed 10,000 symphonies. I could say the program is the work of art, and these few lines of code contain 10,000 I Ching symphonies! A “generative” work, much as LaMonte Young’s single sentence, “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It,” “generated” the first Velvet Underground record, which generated a band for every copy sold.

I jest — but let us ask, what really is the difference between these two ways of composing John Cage’s works?

Most obviously, I do think the absence of physicality in the composition process matters. It is irreducibly less interesting to abstract a process into an algorithm and realize it digitally than to physically perform it. And intertwined with this, the obscuration of the process matters. Cage got to follow along, one note at a time, as his works were composed, and we, listening, experience the delight of surprise, imagining his surprised delight. There is no comparable image, to help me focus my attention, in a work produced by the black box of an algorithm.

These differences are surely important, but there is a deeper underlying difference. Rigorous unpredictability only exists in the physical world.

Several times in this article I have used the word “pseudorandom,” and I am using it with intention. There is no randomness in a digital system. Computers are rigidly deterministic — that is their power. A computer program run 1000 times will give the same result 1000 times. It cannot make mistakes, and that is why computers are valuable.

So, in order to actually write the code for our imaginary digital John Cage, we would need to replace the act of tossing a coin (which is already a simplification of the traditional method of sorting yarrow stalks into piles, and actually has a slightly different probability distribution). We would use a built-in “random” number generator packaged with our programming language. Under the hood, it would work by taking a number from the computer’s state, such as the last few digits of the current time measured in milliseconds, and run it through an algorithm, such as the Mersenne Twister algorithm, to generate more digits from that “seed.”

There is nothing random about this procedure however. Milliseconds tick by one at a time in a completely predictable fashion; the output of a Mersenne Twister is invariable. Anyone with access to the logs of our computer could reproduce the exact sequence of digits we used to compose every note of our imaginary 10,000 John Cage symphonies, and they will be the same, note for note.

While, on the other hand, even if I go to Cage’s cottage in Stony Point, New York, and sit at his desk [I could not really do this, sadly, as neither the desk nor the cottage still exist. But we are imagining], and throw the same three I Ching coins he used, every symphony I compose will be different in every respect from any Cage composed during his lifetime.

While, on the other hand, even if I go to Cage’s cottage in Stony Point, New York, and sit at his desk4, and throw the same three I Ching coins he used, every symphony I compose will be different in every respect from any Cage composed during his lifetime.

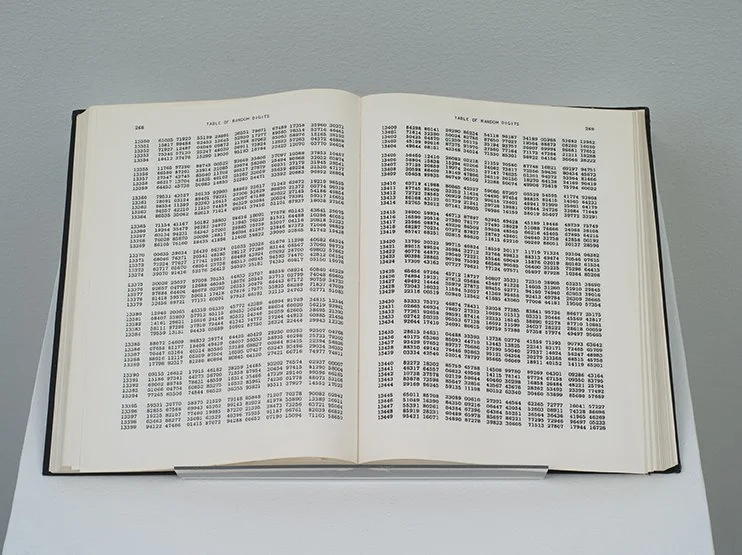

Sacred book of my religion

This is a longstanding problem in computer science, which has been addressed in many ways. The RAND corporation, pet intellectuals of the Pentagon, is called that because its first publication was A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates, which, along with Philips’ A Humument and Eno’s Oblique Strategies, is among my prize possessions. Several technology companies, most famously Cloudflare, use video cameras aimed at lava lamps to generate random numbers in real time. Older computers, with physical hard drives, generated limited random fluctuations by the movement of their read/write heads; modern solid state hard drives do not. The physical elements of computers do fluctuate randomly, or “produce entropy” in computer science jargon, but the problem is they do not produce enough of it fast enough to be computationally useful. Cryptography applications get around this by prompting users to type and move the mouse “at random” so they can harvest the entropy and speed the process along.

This is, in my view, a fundamental distinction between digital and physical tools, and one that is underappreciated. Not only do the algorithms that increasingly run our lives — as well as underpin Eno’s “generative” artworks — hide their internal processes from us, presenting us only with an output; they are also either deterministic, or they are inefficient, or they are expensive.

And when, as is almost always the case, they are both hidden and deterministic, they are subject to perverse incentives. They cost money to make and must be used to extract money, and if they can do so by manipulating their users, they will.

A Global Business Network

Which brings us to Eno’s relationship with Stewart Brand and the Long Now Foundation, which Eno christened5. Penman takes a dim view of Long Now. He observes its origins in the murky Global Business Network, a consultancy founded by Peter Schwartz in the 80s. Schwartz’s product — which he developed based on work by Herman Kahn6 at the aforementioned RAND Corporation, oddly enough — is called “scenario planning,” and Penman is right that governments and corporations are the natural customers.

But “scenario planning,” as outlined in GBN cofounder Jay Ogilvie’s lovely little book Facing the Fold, is pretty generally applicable, benign, and value-neutral. As a methodology it is equally useful to individuals — even revolutionaries! — as it was to Shell Oil Company, where Schwartz and Ogilvie met. The formal problem, of course, is that individuals cannot afford the services of scenario planners; and so if you want to do scenario planning for a living you are going to have to find customers with money.

And if you want to keep those customers, you are going to be under increasing pressure to tell them what they want to hear.

This, in my view, is the simplest explanation for the trajectory of Stewart Brand himself, and of the Long Now Foundation. It is all very well to concern yourself with the openminded exploration of big ideas, and the very long-term future of society; but at some point someone is going to have to pay to keep the lights on. Building a 10,000 year clock is a wonderful, poetic idea, but you are going to need Jeff Bezos’ land (and money), or it’s going to stay in the realm of ideas. And, as it turns out, neither your clients nor your donors want to hear negative forecasts. They may say they do — but the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and over the years, you are going to discover that your donations and payments are higher when you offer rose-colored depictions of a coming 1000-year reich of abundance than they are when you warn of climate catastrophe, much less the internal contradictions of capitalism.

All this, I think, is what Brand meant by his appallingly callous and naïve bon mot: “You are either part of the steamroller, or you’re part of the road.” Brand, and his cronies, decided it was a fool’s game to try to stop the steamroller of technocapitalism — or even to deflect it. Better to hop in the cab, where you may have a real chance of impacting the steering somewhat.

Except, in actual fact, the steering compartment is locked. The drivers are not accepting passengers, much less copilots. The only available spots are hanging precariously onto the sides, watching helplessly as your former friends are crushed beneath the wheels.

This is what it is to offer “consulting services” in “scenario planning” to governments and corporations. It is to make a career of clinging desperately to a destructive machine which is being driven by someone else, sycophantically buttering up the driver and hoping he can hear you over the noise of the grinding gears.

This is also the import of GBN and Long Now board member Kevin Kelly’s book title, What Does Technology Want? It is an act of strategic misdirection. By anthropomorphizing the abstraction, “technology,” Kelly is performing an important service: He is hiding from view the people who benefit from that abstraction, and the economic system that supports them. There is another book, as yet unwritten, called What Do Technocapitalists Want? But we all know what they want. They want money, sex and power. The question is how easily are we going to give it to them.

There are other, darker undercurrents to the Long Now crowd. They are all represented by the same literary agent, long-time Brand associate John Brockman. Brockman was also7 intellectual enabler to one Jeffrey Epstein; until his death Epstein bankrolled Brockman’s Edge Foundation, which functioned as the main network supplying Epstein with the (always apolitical, always techno-optimist) contemporary intellectuals that gave him cover. Indeed, Brockman and Epstein were close enough that Brockman attended a dinner celebrating Epstein’s release from prison, as recorded by none other than (former) Prince Andrew.

Conspiracy theories are boring, and intellectually lazy. Like black-box algorithms, they hide complexity and patterns inside shiny oversimplified packages. The connections among Epstein, Brockman, Schwartz, and Brand (and Eno) are the traces of perverse incentives; more the desperate acts of men hoping to hold on to relative comfort and security than sinister plots of secret chiefs. Some want sex, some want money, some want power and prestige; all are in the market to trade what they have for what they don’t. And at root, they all must hustle to survive. This is how we can understand Brand’s trajectory, from “Why haven’t we seen a picture of the whole earth yet?” and the CoEvolution Quarterly to “If you’re not part of the steamroller then you’re part of the road” and the Global Business Network; and it is a trajectory that has also carried our hero Brian Eno along, willy-nilly.

Systems Thinking

The sinister Mr Brockman, in a book published in 1969, when Stewart Brand was still hanging out with the Merry Pranksters, tells of being given a copy of Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics by our friend John Cage, who said only “this is for you8.” Eno was introduced to cybernetics at Ipswich Art College around the same time, by visionary goofball Roy Ascott, whose idea of art instruction was instruction in everything but art. The year before, Eno’s friend and collaborator Peter Schmidt — remember him? — cocurated an exhibit9 at the ICA in London with the wonderful title Cybernetic Serendipity.

More evidence of a conspiracy perhaps. Or simply a case of cybernetic serendipity. Wiener’s ideas were clearly in the air. Wiener was interested, broadly, in whole systems, social, mechanical, and otherwise; in the feedback mechanisms that caused them to maintain homeostasis, or depart from it.

Eno was even more influenced by Wiener’s younger colleague Stafford Beer. In the early Seventies Beer was invited by the government of Salvador Allende to use cybernetic principles to rationalize and decentralize Chilean government; a utopian project that came to a sudden halt in 1973 with the bloody coup of General Augusto Pinochet, tacitly supported by the Nixon administration.

The next year Eno first read Beer’s The Brain of the Firm, and was so taken by it that he contacted the author, and they visited each other several times. Beer, by that time, had retreated into semi-seclusion, attempting, perhaps unsuccessfully, to digest the tragedy of the Chilean experiment. Just as Beer had adapted Wiener’s principles to governments and corporations, Eno adapted Beer’s principles to aesthetics. “Instead of trying to specify it in full detail," Beer wrote in The Brain of the Firm, "you specify it only somewhat. You then ride on the dynamics of the system in the direction you want to go.” This could be read as a restatement of LaMonte Young’s “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It” — or anyway that is how Eno understood it.

Beer is quite clear-eyed about the danger of algorithmic manipulation, and his lifework was designing systems to preserve liberty and support human flourishing. The tragedy — of course — is that, while we can design such systems to our hearts’ content, there has proven to be no incentive to actually build them. This is the lesson of Chile. First, we would need to build some kind of metasystem which incentivized the construction of systems which preserved liberty and supported human flourishing. But, sadly, there is no incentive to build such a metasystem either.

And so the world we live in is precisely the dystopia envisioned by Beer. Already in 1974, when packet-switching protocols were cutting edge and the internet still just a wild vision, he wrote:

“What is to be done with cybernetics, the science of effective organization? Should we all stand by complaining, and wait for someone malevolent to take it over and enslave us? An electronic mafia lurks around that corner.”

And lurk, indeed, they did; like a ghost in the machine, the dystopian potential of technocratic rule lay nascent, like a poison seed, and the process of its blossoming is likely not complete.

For, if you think about it, there is a conflict within cybernetics from the very outset. The subtitle of Wiener’s book — Control and Communication in Animal and Machine — already reveals it. Is cybernetics the science of communication? Or of control?

Even the word is ambiguous. Κυβερνετεσ, kybernetes, in classical Greek means “helmsman” — but the English cognate is “governor.” And the example that Wiener had in mind was the “Watt centrifugal governor,” a simple and elegant mechanism which uses the speed of a steam engine to directly control the flow of steam: As the engine speed increases, the flow of steam is mechanically reduced, causing the speed to decrease, causing the flow of steam to increase again. Once calibrated, the Watt governor will oscillate around a desired point of homeostasis, all on its own.

Wiener was fascinated by this device precisely because it is self-contained; no one has to measure the engine’s speed, no one must constrict the flow of steam; it is self-managing. Is it, then, an example of control, or of communication? Or is it, rather, some other kind of phenomenon altogether? Does the steam governor “know” how fast it is spinning? Or does it, simply, spin? Much hangs in the balance.

The steam governor has served as metaphor in two other contexts (that I know of): Alfred Russell Wallace, in the paper that inspired Darwin to publish On the Origin of Species, used it as an example of the principle of natural selection, which, like the steam governor, operates autonomously and without intention; and JJ Gibson used it to explain his concept of ecological cognition. For Gibson, it is not necessary to posit a flow of “information” about the environment, which is then processed somehow by the brain which spits out a decision. Rather, like the steam governor, it is possible to conceive of a being and its environment as tightly coupled, with the being’s behavior an emergent property of the whole system; cognition is not “in” a person, “about” the environment — but located “in” the whole system of person and environment together.

This matters: The question of “where is the governor” is one that remains strategically unanswered in much “systems thinking.” Brockman client Kevin Kelly’s first book, Out of Control, amounts to a dumbing down and strategic repurposing of cybernetic ideas to convince the reader that oppression by technology firms is Good, Actually, and consumers should not concern themselves with decision-making, other than deciding what to buy.

Absent, in general, from “systems thinking” is any reference to, or apparent awareness of, that great systems thinker Karl Marx; capitalism is grandfathered in, the market’s invisible hand is there to be marveled at but not questioned. Eno references eugenicist Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”; he appears unaware of the work of Elinor Ostrum and many others who have shown how social norms, outside the market, allowed commons to exist without tragedy for millennia before the advent of capitalism.

And that is the other blind spot of “systems thinking,” at least as practiced by the Long Now Foundation and its fellow travelers: Ecology. The “systems” about which they “think” are by definition bounded. Their boundedness allows them to be managed, engineered, allows interventions from without to nudge them towards a steady state.

Ecological systems, unfortunately, exhibit no such neatness. There is no inherent limit on the number of significant variables in an ecological system. Thus their responses to interventions are, must be, unpredictable — there is no way in advance to know which variables will be affected, since the variables themselves are rigorously indeterminate. This basic aspect of ecological literacy means that the Law of Unintended Consequences is really that, a Law.

Stewart Brand, however, does not see things this way. Another of his aphorisms goes like this: “We are as Gods, so we might as well get good at it10.” This Faustian claim of infinite power and the infinite wisdom to use it appears to be naïve incoherent hubris to anyone aware of ecological reality; but it is, of course, extremely pleasing to Brand’s masters, driving the steamroller on which he rides, emblazoned on its sides with the title of Norbert Wiener’s second book, The Human Use of Human Beings.

Ecological systems are truly ungovernable, out of control. They cannot be managed, engineered, or even steered with any accuracy. Not from outside anyway; and whether there is some steering mechanism, some Governor, some Helmsman, within them is a question best left to theologians11.

The technoutopian fantasies of Kelly and Brand thus turn reality precisely upside down. Reifying and anthropomorphizing “technology,” pretending it is a force independent of the venal humans whose tool it is, fetishizing it (in both the Marxian and Freudian senses), they believe — or pretend to believe, to please their paymasters — that it is “out of control,” an ungoverned governor. Meanwhile, the ecological systems in which we are all embedded, the complexity of which is such that they are in a simple and rigorous sense unmanageable, with behavior that is, and will forever be, unpredictable: These, in their delirium, they claim to manage. Or in any case they have learned there is money to be made selling that claim.

The Age of the Algorithm

“History is what hurts.”

Somewhere around 1000 BCE, the divination system called 易經, yijing, a binary logic of 26 or 64 symbols was evolved. 3000 years later John Cage, a student of Daoism and Zen, used it to compose music that almost no one would listen to, but was no less influential for that. A similar binary logic was utilized in electronic computers, one byte of information being equal to 8 bits encoding 28 or 256 possible combinations.

In or around 1656 Christiaan Huygens invented a cetntrifugal regulator; 100 years later James Watt adapted the mechanism to the steam engine, calling it a “governor.” 200 years after that, Norbert Wiener used the Greek root to coin the neologism “cybernetic”; some decades later science fiction author William Gibson borrowed the first half for his own neologism, “cyberspace,” and eventually the prefix “cyber-” came to mean anything pertaining to the internet.

And Brian Eno … coming of age and attaining fame in the age of television, the vacuum tubes of which vibrated with life-affirming entropy, he was cursed, as were we all, to survive into the age of the algorithm.

“Algorithm,” the mathematical formalism, has, over his lifetime (and mine), been supplanted by “algorithm,” the social function. For, as Stafford Beer constantly reiterated, “the purpose of a system is what it does”; and what algorithms do is hide.

Algorithms cloak their governors in a cloud of obscurity, making their interventions in our lives appear neutral, autonomous, ungoverned. Algorithms mask control as communication. Algorithms present the pseudorandom as truly random; feign surprise at what was, in fact, predetermined.

And, in the age of the algorithm, our childlike delight in the surprising (and inherently unpredictable) evolution of a simple process — incense smoke swirling as it rises, wax flowing gracefully in a lava lamp — has been replaced, while we weren’t looking, with a cheap plastic simulacrum: A YouTube video on repeat, gaudy pictures on a screen meant to distract us from what is really going on, off-screen.

No one intended for it to turn out like this. Everyone was just trying to get by. The incentives, however, were not questioned. And now the incentives are encoded in the algorithm itself, and are immortal.

Over his long, productive lifetime, it is not that Eno’s art has become less inspired; rather the technological context in which he is working has changed in such a way as to render inspiration impossible.

The process will be complete when our only choices will be choices about what to buy. Then, no one will remember the difference between making and buying; the only “artistic” act left to us will be the purchase of an “artistic” product — perhaps Brian Eno’s little book, What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory.

-

I wrote a little about this, actually, here: https://smallfires.cc/moonflower-farm-occasional-dispatches/gomd ↩

-

As it was on me; I played it for my friends during a very memorable acid trip aged 18 or so. ↩

-

A mutual friend of Eno and Philips, who did paintings based on the I Ching hexagrams — it all falls into place. ↩

-

I could not really do this, sadly, as neither the desk nor the cottage still exist. But we are imagining. ↩

-

Perhaps after Fernand Braudel’s method of longue durée history — Eno mentions Braudel from time to time. ↩

-

or “Conman Herm” as we used to call him. ↩

-

in the words of his ex-client Evgeny Morozov. ↩

-

It all falls into place. ↩

-

Featuring Cage among others. ↩

-

An aphorism that provides the title for a recent biopic on Brand, with soundtrack by none other than Brian Eno. ↩

-

I can’t resist hinting that such theological, or “atheological,” speculations form a significant part of my book, A Provisional Manual of West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druidry, which you can buy here and should. ↩