“These judgments should lead to silence yet I write. This is not paradoxical.”

-George Bataille

On Brian Eno — a Reply to Ian Penman

Brian Eno has written a book!

Well maybe not a book exactly — not a book as we formerly understood it, a cohesive text on a single subject to be read over the course of a few evenings in front of the fire. More of a talismanic object — a “book.” Ready to take its place on the display table of the bookstore alongside Rubin’s The Creative Act, Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish, Byrne’s How Music Works; talismanic objects which need not be read, but purchased, and which promise, through that purchase, to reaffirm that the purchaser is still, despite everything, creative.

Eno’s entry — What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory — is especially comforting in this regard, as it reassures the reader that pretty much everything humans do, from posting selfies to cooking meals, is actually Art. Everything, perhaps, except online shopping. We will return to this.

Ian Penman, in a characteristically delightful and nuanced review, mostly ignores the book, instead taking the opportunity to celebrate Eno’s greatness, and to mourn his decline over the last half century. It is an elegy for a certain kind of genius, and for the world into which Eno, Penman, and I myself were born. But after reading it, I could not shake the feeling that it was unfair to Eno, and overly fair to the world.

I am probably of an age with Penman, and, like him, Eno is one of my last surviving heroes. Penman only really rates his earliest work. He already considers 1977’s Before and After Science to be “insipid.” Myself I would place Eno’s descent into irrelevance somewhat later; I was young enough to cry myself to sleep, suffering my first heartbreak, listening to Ambient 4: On Land, and it is only a couple years after that, with the release of Apollo, that I began to lose interest.

Be that as it may, these are subjective aesthetic judgments; Penman’s first moral critique concerns the 1981 collaboration with David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Penman doesn’t like the music on this record; I happen to disagree. My wife and I relistened to it last week and it’s amazing; as we remarked to one another, it’s not even correct to call it ahead of its time, because there’s really not been anything like its scritchy, looping, layered, polyrhythmic jerking trance funk since.

Penman takes issue with the record’s use of “samples” — which is, first of all, an anachronism. The samplers available in 1981 could only hold 128 kb of memory, nowhere near enough for the extended vocal collages of “Jezebel Spirit” and “Moonlight in Glory”; and in any case no such device was used. The “found” vocals are added the old way, with magnetic tape.

Method aside, what Penman wants to take Eno and Byrne to task for is exoticising, appropriating, taking credit for the creativity of others. This is I think a little ungenerous. There are, to be sure, fraught questions raised by sampling technology; but they can hardly be laid at the door of Brian Eno and David Byrne [I wrote a little about this, actually, here: https://smallfires.cc/moonflower-farm-occasional-dispatches/gomd]. They may have built a song around a recording of Lebanese singer Dunya Yusin without credit, which was admittedly not cool; but to do so they had to physically stop and start a tape deck, cut and splice, lean on the flanges to change the speed, all the lost art of analog recording, and this in an era before the ubiquity of sampling made music licensing an entire field of corporate law.

And that is my fundamental contribution to the lament. What has changed is not Brian Eno, polymath, curious tinkerer with new technology; it is the technologies available for tinkering, and the culture they have created in their wake.

Penman reserves most of his ire for Eno’s “generative” works — “software to systematize (and cage, and kill) playfulness.” I don’t disagree. It is hard to care about a series of 10,000 “paintings” produced on screens by a few lines of pseudorandom code — effectively, as Penman points out, a screensaver. But I think it’s worth investigating. How is the notion of “generative art” different now, in the era of the algorithm, than it once was — when Eno (and Penman and I) first became interested in it?

I attended a panel discussion with Eno — I think at the Exploratorium in San Francisco in 1999 or so, though I’m not sure now, the years have blunted my memory somewhat — where he said something that stayed with me ever since. He was describing his then current collaborative project, developing software to generate sound; and how he turned to his collaborator, I forget who it was, after working with the code for hours, and said, “Want to take a break? And just make some … muh … muh …” And, Eno said, they had both been working on the code for so long that neither one of them could even quite say the word, “music.”

At the time, it seemed to me that Eno was recognizing he had gone a little way down a path which was going to become a cul-de-sac. In the event, he did not turn back.

Generative Music

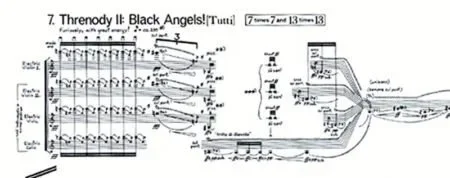

“Generative Music” is a tradition of Modernist (and Postmodernist) composition, composers who wanted to wrest final control over the music from their own hands, to divest, to liberate. Charles Ives left sections of compositions up to the players, marking the score “ad libitum”; Lamonte Young made an early Fluxus work the entire text of which is “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It.” George Crumb’s and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s graphic scores, the interpretation of which was left up to the players, would find a place in this genealogy, as would, certainly, John Cage’s “aleatoric” compositions.

Cage used a couple of different strategies, wishing to be surprised by the music he composed; most painstaking were several compositions in which he determined successive notes by throwing the I Ching. And Steve Reich’s “phasing music” has a place here too; “Come Out,” 16 tape loops of a black radical saying, “I had to, let some of the bruise blood come out to show them” going out of phase with one another over the course of an incredibly psychedelic 20 minutes was a big influence on the young Eno [As it was on me; I played it for my friends during a very memorable acid trip aged 18 or so]. Reich’s other early works, like “Clapping Music,” are also “generative” in the strict sense: Simple rhythmic or musical patterns are allowed to drift in and out of phase with one another according to (also simple) predetermined rules, resulting in music that would be very, very complicated to notate in the traditional manner.

This is work which emphasizes the “process” of composition, and in the analog era these were physical processes that took the time they took. Cage methodically throwing 3 coins, building up a hexagram, over and over again, note after note; Reich cutting the tape, splicing the loops, pressing play on 16 decks and watching it unroll.

How different in the digital era. Cage’s entire discography could be produced with a few lines of code and the push of a button; Reich’s experiments similarly. It would be comical to call such works “process” compositions, were they made today, with the tools available. “Generative” — okay. They’re undeniably “generative.” But what has been lost in the transition from “process” to “generative?”

Penman observes that Eno was influenced by his older friend, the painter Tom Philips. Philips’ masterwork is the book A Humument. To make this work, Philips set himself a simple limitation: He would buy the first used book he could find for threepence, and paint over it. The book he found, a Victorian novel called A Human Document, had wide rivers of type, and Philips spent the next 50 years painting elaborate miniatures over every page, leaving unpainted words and parts of words that reveal a new story buried within the original text. As the work progressed, Philips decided, or discovered, that the protagonist was named Bill Toge; and so a new rule emerged: Every time he encountered words like “together” or “altogether,” these became appearances of the hero.

The whole book is this beautiful

How would you do something like this in the digital era? Is it possible?

And if it’s possible, is it interesting? Write a few lines of code and press a button?

Penman doesn’t discuss Oblique Strategies, one of Eno’s most enduring productions: A box of 55 cards with gnomic suggestions for overcoming creative obstacles, composed with painter Peter Schmidt [A mutual friend of Eno and Philips, who did paintings based on the I Ching hexagrams — it all falls into place]. Here we encounter maybe the most stark example. Over the years, several people have decided, out of a desire to democratize access to this (extremely useful and beautiful) work, normally available only in limited printed editions, to make an app: You guessed it, a few lines of Javascript, pseudorandomly shuffling Eno and Schmidt’s inspiring phrases.

Something has been gained — accessibility. Something has been lost — perhaps not much, but something nevertheless. The process. The process of stopping, shuffling, picking a card, has been reduced to a deterministic algorithm, and hidden, like all algorithms, out of sight of the user.

The Random and the Pseudorandom

I have, personally, always loved watching physical processes unfold. Raindrops running down the windshield, candle wax dripping on a wine bottle. Grains of sand landing in a pile. I don’t think I am alone in this. However, it is not just the unfolding of a process that delights me. It is the element of surprise, the “aleatory,” as Cage would say. There is, actually, nothing particularly delightful about observing a purely deterministic process play out: A screensaver, say. The date and time, in Helvetica, drift across the screen, “bouncing” (according to predetermined rules) when they reach the screen’s edge. I have whiled away some minutes of my life watching processes like these, and they are minutes I will never get back, and it’s a damn shame.

Watching (or listening to) an aleatoric process, the outcome of which is rigorously uncertain, my mind wanders, in a kind of trance, and new, surprising ideas occur. I am musing, woolgathering. Watching a screensaver at the doctor’s office, my mind is forced into a rutted road to nowhere. I am nowhere surprised by what occurs to me. It is only an endless rehearsal of the known; something to look at while I wait for anything else to happen.

John Cage threw the I Ching, over and over, for hours a day, and added the notes it determined to a physical pad of ledger paper. I could, right now, code an I Ching composition bot to produce an entire symphony — or indeed 10,000 symphonies. I could say the program is the work of art, and these few lines of code contain 10,000 I Ching symphonies! A “generative” work, much as LaMonte Young’s single sentence, “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It,” “generated” the first Velvet Underground record (via his student John Cale), which generated a band for every copy sold.

I jest — but let us ask, what really is the difference between these two ways of composing John Cage’s works?

Most obviously, I do think the absence of physicality in the composition process matters. It is irreducibly less interesting to abstract a process into an algorithm and realize it digitally than to physically perform it. And intertwined with this, the obscuration of the process matters. Cage got to follow along, one note at a time, as his works were composed, and we, listening, experience the delight of surprise, imagining his surprised delight. There is no comparable image, to help me focus my attention, in a work produced by the black box of an algorithm.

These differences are surely important, but there is a deeper underlying difference. Rigorous unpredictability only exists in the physical world.

Several times in this article I have used the word “pseudorandom,” and I am using it with intention. There is no randomness in a digital system. Computers are rigidly deterministic — that is their power. A computer program run 1000 times will give the same result 1000 times. It cannot make mistakes, and that is why computers are valuable.

So, in order to actually write the code for our imaginary digital John Cage, we would need to replace the act of tossing a coin (which is already a simplification of the traditional method of sorting yarrow stalks into piles, and actually has a slightly different probability distribution). We would use a built-in “random” number generator packaged with our programming language. Under the hood, it would work by taking a number from the computer’s state, such as the last few digits of the current time measured in milliseconds, and run it through an algorithm, such as the Mersenne Twister algorithm, to generate more digits from that “seed.”

There is nothing random about this procedure however. Milliseconds tick by one at a time in a completely predictable fashion; the output of a Mersenne Twister is invariable. Anyone with access to the logs of our computer could reproduce the exact sequence of digits we used to compose every note of our imaginary 10,000 John Cage symphonies, and they will be the same, note for note.

While, on the other hand, even if I go to Cage’s cottage in Stony Point, New York, and sit at his desk [I could not really do this, sadly, as neither the desk nor the cottage still exist. But we are imagining], and throw the same three I Ching coins he used, every symphony I compose will be different in every respect from any Cage composed during his lifetime.

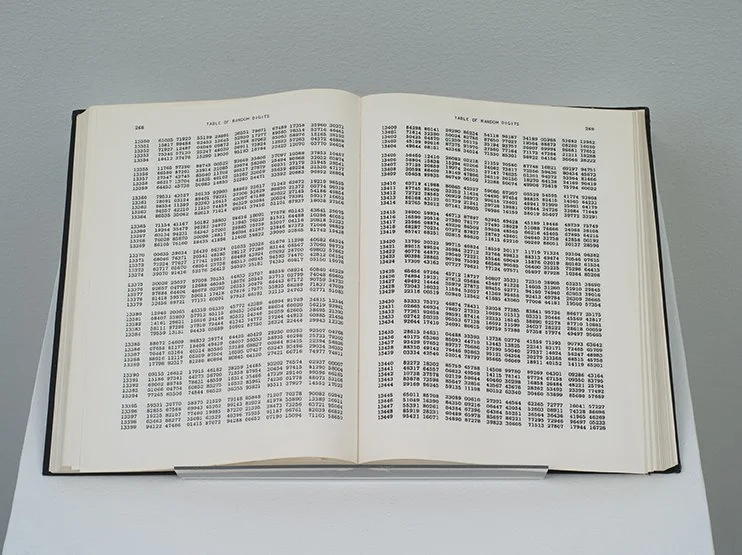

Sacred book of my religion

This is a longstanding problem in computer science, which has been addressed in many ways. The RAND corporation, pet intellectuals of the Pentagon, is called that because its first publication was A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates, which, along with Philips’ A Humument and Eno’s Oblique Strategies, is among my prize possessions. Several technology companies, most famously Cloudflare, use video cameras aimed at lava lamps to generate random numbers in real time. Older computers, with physical hard drives, generated limited random fluctuations by the movement of their read/write heads; modern solid state hard drives do not. The physical elements of computers do fluctuate randomly, or “produce entropy” in computer science jargon, but the problem is they do not produce enough of it fast enough to be computationally useful. Cryptography applications get around this by prompting users to type and move the mouse “at random” so they can harvest the entropy and speed the process along.

This is, in my view, a fundamental distinction between digital and physical tools, and one that is underappreciated. Not only do the algorithms that increasingly run our lives — as well as underpin Eno’s “generative” artworks — hide their internal processes from us, presenting us only with an output; they are also either deterministic, or they are inefficient, or they are expensive.

And when, as is almost always the case, they are both hidden and deterministic, they are subject to perverse incentives. They cost money to make and must be used to extract money, and if they can do so by manipulating their users, they will.

A Global Business Network

Which brings us to Eno’s relationship with Stewart Brand and the Long Now Foundation, which Eno christened [Perhaps after Fernand Braudel’s method of longue durée history — Eno mentions Braudel from time to time]. Penman takes a dim view of Long Now. He observes its origins in the murky Global Business Network, a consultancy founded by Peter Schwartz in the 80s. Schwartz’s product — which he developed based on work by Herman Kahn [or “Conman Herm” as we used to call him] at the aforementioned RAND Corporation, oddly enough — is called “scenario planning,” and Penman is right that governments and corporations are the natural customers.

But “scenario planning,” as outlined in GBN cofounder Jay Ogilvie’s lovely little book Facing the Fold, is pretty generally applicable, benign, and value-neutral. As a methodology it is equally useful to individuals — even revolutionaries! — as it was to Shell Oil Company, where Schwartz and Ogilvie met. The formal problem, of course, is that individuals cannot afford the services of scenario planners; and so if you want to do scenario planning for a living you are going to have to find customers with money.

And if you want to keep those customers, you are going to be under increasing pressure to tell them what they want to hear.

This, in my view, is the simplest explanation for the trajectory of Stewart Brand himself, and of the Long Now Foundation. It is all very well to concern yourself with the openminded exploration of big ideas, and the very long-term future of society; but at some point someone is going to have to pay to keep the lights on. Building a 10,000 year clock is a wonderful, poetic idea, but you are going to need Jeff Bezos’ land (and money), or it’s going to stay in the realm of ideas. And, as it turns out, neither your clients nor your donors want to hear negative forecasts. They may say they do — but the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and over the years, you are going to discover that your donations and payments are higher when you offer rose-colored depictions of a coming 1000-year reich of abundance than they are when you warn of climate catastrophe, much less the internal contradictions of capitalism.

All this, I think, is what Brand meant by his appallingly callous and naïve bon mot: “You are either part of the steamroller, or you’re part of the road.” Brand, and his cronies, decided it was a fool’s game to try to stop the steamroller of technocapitalism — or even to deflect it. Better to hop in the cab, where you may have a real chance of impacting the steering somewhat.

Except, in actual fact, the steering compartment is locked. The drivers are not accepting passengers, much less copilots. The only available spots are hanging precariously onto the sides, watching helplessly as your former friends are crushed beneath the wheels.

This is what it is to offer “consulting services” in “scenario planning” to governments and corporations. It is to make a career of clinging desperately to a destructive machine which is being driven by someone else, sycophantically buttering up the driver and hoping he can hear you over the noise of the grinding gears.

This is also the import of GBN and Long Now board member Kevin Kelly’s book title, What Does Technology Want? It is an act of strategic misdirection. By anthropomorphizing the abstraction, “technology,” Kelly is performing an important service: He is hiding from view the people who benefit from that abstraction, and the economic system that supports them. There is another book, as yet unwritten, called What Do Technocapitalists Want? But we all know what they want. They want money, sex and power. The question is how easily are we going to give it to them.

There are other, darker undercurrents to the Long Now crowd. They are all represented by the same literary agent, long-time Brand associate John Brockman. Brockman was also "intellectual enabler" [in the words of his ex-client Evgeny Morozov] to one Jeffrey Epstein; until his death Epstein bankrolled Brockman’s Edge Foundation, which functioned as the main network supplying Epstein with the (always apolitical, always techno-optimist) contemporary intellectuals that gave him cover. Indeed, Brockman and Epstein were close enough that Brockman attended a dinner celebrating Epstein’s release from prison, as recorded by none other than (former) Prince Andrew.

Conspiracy theories are boring, and intellectually lazy. Like black-box algorithms, they hide complexity and patterns inside shiny oversimplified packages. The connections among Epstein, Brockman, Schwartz, and Brand (and Eno) are the traces of perverse incentives; more the desperate acts of men hoping to hold on to relative comfort and security than sinister plots of secret chiefs. Some want sex, some want money, some want power and prestige; all are in the market to trade what they have for what they don’t. And at root, they all must hustle to survive. This is how we can understand Brand’s trajectory, from “Why haven’t we seen a picture of the whole earth yet?” and the CoEvolution Quarterly to “If you’re not part of the steamroller then you’re part of the road” and the Global Business Network; and it is a trajectory that has also carried our hero Brian Eno along, willy-nilly.

Systems Thinking

The sinister Mr Brockman, in a book published in 1969, when Stewart Brand was still hanging out with the Merry Pranksters, tells of being given a copy of Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics by our friend John Cage, who said only “this is for you.” [It all falls into place.] Eno was introduced to cybernetics at Ipswich Art College around the same time, by visionary goofball Roy Ascott, whose idea of art instruction was instruction in everything but art. The year before, Eno’s friend and collaborator Peter Schmidt — remember him? — cocurated an exhibit [Featuring Cage among others] at the ICA in London with the wonderful title Cybernetic Serendipity.

More evidence of a conspiracy perhaps. Or simply a case of cybernetic serendipity. Wiener’s ideas were clearly in the air. Wiener was interested, broadly, in whole systems, social, mechanical, and otherwise; in the feedback mechanisms that caused them to maintain homeostasis, or depart from it.

Eno was even more influenced by Wiener’s younger colleague Stafford Beer. In the early Seventies Beer was invited by the government of Salvador Allende to use cybernetic principles to rationalize and decentralize Chilean government; a utopian project that came to a sudden halt in 1973 with the bloody coup of General Augusto Pinochet, tacitly supported by the Nixon administration.

The next year Eno first read Beer’s The Brain of the Firm, and was so taken by it that he contacted the author, and they visited each other several times. Beer, by that time, had retreated into semi-seclusion, attempting, perhaps unsuccessfully, to digest the tragedy of the Chilean experiment. Just as Beer had adapted Wiener’s principles to governments and corporations, Eno adapted Beer’s principles to aesthetics. “Instead of trying to specify it in full detail," Beer wrote in The Brain of the Firm, "you specify it only somewhat. You then ride on the dynamics of the system in the direction you want to go.” This could be read as a restatement of LaMonte Young’s “Draw a Straight Line and Follow It” — or anyway that is how Eno understood it.

Beer is quite clear-eyed about the danger of algorithmic manipulation, and his lifework was designing systems to preserve liberty and support human flourishing. The tragedy — of course — is that, while we can design such systems to our hearts’ content, there has proven to be no incentive to actually build them. This is the lesson of Chile. First, we would need to build some kind of metasystem which incentivized the construction of systems which preserved liberty and supported human flourishing. But, sadly, there is no incentive to build such a metasystem either.

And so the world we live in is precisely the dystopia envisioned by Beer. Already in 1974, when packet-switching protocols were cutting edge and the internet still just a wild vision, he wrote:

“What is to be done with cybernetics, the science of effective organization? Should we all stand by complaining, and wait for someone malevolent to take it over and enslave us? An electronic mafia lurks around that corner.”

And lurk, indeed, they did; like a ghost in the machine, the dystopian potential of technocratic rule lay nascent, a poison seed, and the process of its blossoming is likely not complete.

For, if you think about it, there is a conflict within cybernetics from the very outset. The subtitle of Wiener’s book — Control and Communication in Animal and Machine — already reveals it. Is cybernetics the science of communication? Or of control?

Even the word is ambiguous. Κυβερνετεσ, kybernetes, in classical Greek means “helmsman” — but the English cognate is “governor.” And the example that Wiener had in mind was the “Watt centrifugal governor,” a simple and elegant mechanism which uses the speed of a steam engine to directly control the flow of steam: As the engine speed increases, the flow of steam is mechanically reduced, causing the speed to decrease, causing the flow of steam to increase again. Once calibrated, the Watt governor will oscillate around a desired point of homeostasis, all on its own.

Wiener was fascinated by this device precisely because it is self-contained; no one has to measure the engine’s speed, no one must constrict the flow of steam; it is self-managing. Is it, then, an example of control, or of communication? Or is it, rather, some other kind of phenomenon altogether? Does the steam governor “know” how fast it is spinning? Or does it, simply, spin? Much hangs in the balance.

The steam governor has served as metaphor in two other contexts (that I know of): Alfred Russell Wallace, in the paper that inspired Darwin to publish On the Origin of Species, used it as an example of the principle of natural selection, which, like the steam governor, operates autonomously and without intention; and JJ Gibson used it to explain his concept of ecological cognition. For Gibson, it is not necessary to posit a flow of “information” about the environment, which is then processed somehow by the brain which spits out a decision. Rather, like the steam governor, it is possible to conceive of a being and its environment as tightly coupled, with the being’s behavior an emergent property of the whole system; cognition is not “in” a person, “about” the environment — but located “in” the whole system of person and environment together.

This matters: The question of “where is the governor” is one that remains strategically unanswered in much “systems thinking.” Brockman client Kevin Kelly’s first book, Out of Control, amounts to a dumbing down and strategic repurposing of cybernetic ideas to convince the reader that oppression by technology firms is Good, Actually, and consumers should not concern themselves with decision-making, other than deciding what to buy.

Absent, in general, from “systems thinking” is any reference to, or apparent awareness of, that great systems thinker Karl Marx; capitalism is grandfathered in, the market’s invisible hand is there to be marveled at but not questioned. Eno references eugenicist Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”; he appears unaware of the work of Elinor Ostrum and many others who have shown how social norms, outside the market, allowed commons to exist without tragedy for millennia before the advent of capitalism.

And that is the other blind spot of “systems thinking,” at least as practiced by the Long Now Foundation and its fellow travelers: Ecology. The “systems” about which they “think” are by definition bounded. Their boundedness allows them to be managed, engineered, allows interventions from without to nudge them towards a steady state.

Ecological systems, unfortunately, exhibit no such neatness. There is no inherent limit on the number of significant variables in an ecological system. Thus their responses to interventions are, must be, unpredictable — there is no way in advance to know which variables will be affected, since the variables themselves are rigorously indeterminate. This basic aspect of ecological literacy means that the Law of Unintended Consequences is really that, a Law.

Stewart Brand, however, does not see things this way. Another of his aphorisms goes like this: “We are as Gods, so we might as well get good at it.” [An aphorism that provides the title for a recent biopic on Brand, with soundtrack by none other than Brian Eno.] This Faustian claim of infinite power and the infinite wisdom to use it appears to be naïve incoherent hubris to anyone aware of ecological reality; but it is, of course, extremely pleasing to Brand’s masters, driving the steamroller on which he rides, emblazoned on its sides with the title of Norbert Wiener’s second book, The Human Use of Human Beings.

Ecological systems are truly ungovernable, out of control. They cannot be managed, engineered, or even steered with any accuracy. Not from outside anyway; and whether there is some steering mechanism, some Governor, some Helmsman, within them is a question best left to theologians. [I can’t resist hinting that such theological, or “atheological,” speculations form a significant part of my book, A Provisional Manual of West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druidry, which you can buy here and should.]

The technoutopian fantasies of Kelly and Brand thus turn reality precisely upside down. Reifying and anthropomorphizing “technology,” pretending it is a force independent of the venal humans whose tool it is, fetishizing it (in both the Marxian and Freudian senses), they believe — or pretend to believe, to please their paymasters — that it is “out of control,” an ungoverned governor. Meanwhile, the ecological systems in which we are all embedded, the complexity of which is such that they are in a simple and rigorous sense unmanageable, with behavior that is, and will forever be, unpredictable: These, in their delirium, they claim to manage.

Or in any case they have learned there is money to be made selling that claim.

The Age of the Algorithm

“History is what hurts.”

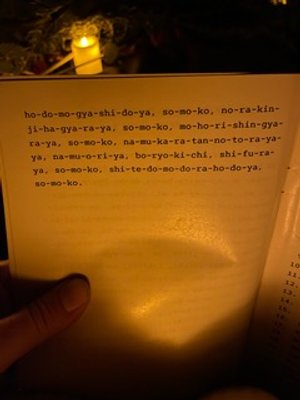

Somewhere around 1000 BCE, the divination system called 易經, yijing, a binary logic of 16 or 64 symbols was evolved. 3000 years later John Cage, a student of Daoism and Zen, used it to compose music that almost no one would listen to, but was no less influential for that. A similar binary logic was utilized in electronic computers, one byte of information being equal to 8 bits encoding 64 or 256 possible combinations.

In or around 1656 Christiaan Huygens invented a cetntrifugal regulator; 100 years later James Watt adapted the mechanism to the steam engine, calling it a “governor.” 200 years after that, Norbert Wiener used the Greek root of that word to coin the neologism “cybernetic”; some decades later science fiction author William Gibson borrowed the first half for his own neologism, “cyberspace,” and eventually the prefix “cyber-” came to mean anything pertaining to the internet.

And Brian Eno … coming of age and attaining fame in the age of television, the vacuum tubes of which vibrated with life-affirming entropy, he was cursed, as were we all, to survive into the age of the algorithm.

“Algorithm,” the mathematical formalism, has, over his lifetime (and mine), been supplanted by “algorithm,” the social function. For, as Stafford Beer constantly reiterated, “the purpose of a system is what it does”; and what algorithms do is hide.

Algorithms cloak their governors in a cloud of obscurity, making their interventions in our lives appear neutral, autonomous, ungoverned. Algorithms mask control as communication. Algorithms present the pseudorandom as truly random; feign surprise at what was, in fact, predetermined.

And, in the age of the algorithm, our childlike delight in the surprising (and inherently unpredictable) evolution of a simple process — incense smoke swirling as it rises, wax flowing gracefully in a lava lamp — has been replaced, while we weren’t looking, with a cheap plastic simulacrum: A YouTube video on repeat, gaudy pictures on a screen meant to distract us from what is really going on, off-screen.

No one intended for it to turn out like this. Everyone was just trying to get by. The incentives, however, were not questioned. And now the incentives are encoded in the algorithm itself, and are immortal.

Over his long, productive lifetime, it is not that Eno’s art has become less inspired; rather the technological context in which he is working has changed in such a way as to render inspiration impossible.

The process will be complete when our only choices will be choices about what to buy. Then, no one will remember the difference between making and buying; the only “artistic” act left to us will be the purchase of an “artistic” product — perhaps Brian Eno’s little book, What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory.

A Toast for this May Eve, 2025 (13-15 Floréal 223)

Tonight I made us Lobster Thermidor. What is a thermidor?

Do you think it’s like a cuspidor? Do you know what a cuspidor is? It’s a spittoon, a receptacle to spit tobacco juice — from Portuguese cuspir, to spit; so I guess on that model a thermidor would be a heater maybe?

Or maybe it’s like a humidor, which you know is a cabinet to keep cigars humid; maybe it’s like a food warmer?

As it turns out, the name of this dish comes from a play; a play called Thermidor that scandalized fin-de-siècle Paris, and was shut down several times. It was so notorious that the chef of a restaurant around the corner invented this dish, for patrons on their way to see the show.

But that doesn’t get us any closer; what was the play about? Well, it was a play about events another hundred years in the past, at the end of the 18th century, in the late years of the French revolution, during what was called the “Thermidorian Reaction.”

Okay, but — what made this reaction “thermidorian?”

To understand that, first we have to recall that Republican France, in their zeal to do away with all superstition, all irrationality, all the remnants of the hierarchical past — the same impulse that led to the metric system in fact — discarded the Gregorian calendar, with its varying length months named after Roman gods and heroes, in favor of a new, rationalized, republican calendar of 12 months of equal length; and one of those months was “Thermidor,” the hot month, about July; and the “Thermidorian Reaction” began on 9 Thermidor 1794, what are called “the events of 9 Thermidor.”

The Republican calendar is mostly forgotten now; one of the only other places a reference to it is preserved is in the title of an essay by Karl Marx, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, which is a pretty baffling title until you know that “Brumaire” is another republican month. Brume means “fog,” so it’s “the foggy month,” around November; and the 18th Brumaire 1799 is the date of the coup which ended the Republican period in France, in which Napoleon Bonaparte seized power. On that day, Napoleon offered a couple leaders of the Republic to help them seize power, and then double-crossed them, in a “coup within a coup,” retaining power for himself, becoming Emperor and setting out upon many other adventures.

Marx’s essay is about events some 60 years later, when Napoleon’s nephew again seized power in France, having his own little “18th Brumaire” — and it is mainly remembered for the first paragraph, which has some great Marx bangers, including “history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce” — which is the point of the whole essay.

Anyway, getting back to Thermidor — what is it that happened five years earlier, on 9 Thermidor, 1794?

To understand that, we have to remember what was happening before, which was called “the Terror.” Revolutionary Maximilian Robespierre, who you probably remember from history class, began as a radically egalitarian member of parliament, who, in his fanatic defense of liberty, equality and fraternity, unleashed a reign of terror in which tens of thousands of citizens were publicly decapitated or died in prison. Robespierre’s secret police were called, with Orwellian panache, the Committee for Public Safety.

Now one of Robespierre’s best deputies was a man named Jean-Lambert Tallien, who was the representative of the Committee for Public Safety in the French port city of Bordeaux, who became known as the “butcher of Bordeaux” because of his enthusiasm for sending people to the guillotine … until he met a woman named Térézia Cabarrus; the hero of our story.

Cabarrus claimed to have been raised by a goat, but in fact she was the daughter of a Basque businessman, who married her at age 14 to a minor French aristocrat, who she detested, and she left him during the revolution, retiring to Bordeaux where she lived a double life, outwardly conventional but secretly helping, by hook or by crook, the steady stream of refugees from Paris who passed through Bordeaux attempting to escape the Terror by emigrating from France.

Cabarrus was evidently possessed of great personal magnetism, because when Tallien, the Butcher of Bordeaux, discovered her activities, instead of arresting her, they became lovers, and from that time on Tallien ceased his oppression of the people of Bordeaux, much to their relief.

Inevitably though, she was found out by Robespierre himself, who had her sent to the most notorious jail of the Republic, which was called La Force; where her lovely hair was hacked off short, and she was stripped of her luxurious bejeweled garments and forced to wear nothing but a simple cotton shift. Robespierre apparently was also taken with her, because he tried to get her to denounce her lover, Tallien, and when she refused Robespierre ordered that every day she be brought a looking glass, so that she could see how her dignity and beauty had been brought low.

Now at the prison of La Force every morning the prisoners were gathered and a list of names was read: The names of those prisoners who were going to be sent to the guillotine that day. And on the day Térézia Cabarrus’s name was read she wrote a letter, which schoolchildren used to memorize, so significant were its effects on French history.

It was a letter to her lover, Jean-Lambert Tallien, and it said: “A courageous man might be able to save my life, by toppling Robespierre, but I find myself condemned by your unworthy cowardice.”

Tallien received the letter, and upon reading it, he called a meeting of the National Assembly, at which he denounced Robespierre, and, because he was the first to dare to do so, others joined him, it sparked a general uprising, Robespierre was captured, and jailed, and eventually sent, himself, to the guillotine; and Térézia Cabarrus was released.

And that is what happened on 9 Thermidor.

After the end of the Terror, Cabarrus was a celebrity; the French called her Notre-Dame de Thermidor, Our Lady of Thermidor. She went to the Jacobin Club, where the Terror had been planned and executed, and symbolically locked the doors. William Pitt, the English Prime Minister, was there, and is supposed to have said “This woman could close the very gates of Hell itself.”

All this should put us in mind, not only of Marx’s dictum — “history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce” — but also of George Santayana’s famous saying, “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Okay, we’re almost done, but there’s a coda. After the end of the Republic Cabarrus became a fashion designer, spreading the latest fashions at her salon; she popularized what we today call the “empire waist” dress, which was a revolution in women’s wear, after the elaborate three piece corseted dresses popular before the Revolution. And she commissioned a painting of herself, in the prison of La Force, hair cropped short, in what was now the latest style, and wearing a shift made not of simple homespun but of luxurious silk and muslin; first as tragedy, then as farce.

So, as we enjoy this delectable dish together, let us remember these events of so long ago; and especially Térézia Cabarrus, Our Lady of Thermidor, who could close the very gates of Hell itself.

Ugh More About Spiritual Teachers

I wrote some thoughts about “spiritual” “teachers” in a Twitter thread a few years ago:

But it turns out I have more to say. I was talking with friend a couple weeks ago who recently left her job at a meditation center and had feelings about it. We pondered, together, whether spiritual teachers are useful, and if so how. And further we asked each other: If you have been practicing for a long time, and have become more settled and present and compassionate and curious than you once were — how do you help? How do you share what you have gathered? For there is no benefit to keeping it. It goes bad if you keep it.

Thinking about all this I began to feel that the phrase “spiritual teacher” is kind of strange. It probably comes from the Japanese 老師, roshi, which in Classical Chinese (from which it migrated into Japanese) meant “old man,” but in modern Mandarin means teacher, albeit with the emphasis on old teacher; Sanskrit गुरु, guru, is usually translated “teacher” but in any other context just means “heavy” or “hard to digest.”

Be that as it may, I am coming to think the word “teacher” is dangerously misleading in this context.

There are realms in which techniques need to be taught, and once mastered, no longer need to be learned. In which one person knows things another person does not, and can write them on a chalkboard, and then both people know them.

Spirituality is not like that. Meditation is not like that.

Meditation instruction takes 20 minutes. For the next 20 years of practice, all a meditation “teacher” can say is “No, you’re probably not going crazy” and “No, you’re probably not enlightened,” followed by, “Keep sitting.”

Which is not to suggest that the relationship formed over those 20 years is unhelpful, shallow, or meaningless. It is, or can be, very, very deep, beautiful beyond words. But — nothing is being taught, and nothing is being learned. Maybe sometimes by example — but even that is rare.

Also, unlike learning a skill, like skateboarding, or algebra, there is no moment when you have “learned” meditation, when your practice of spirituality is “complete,” when you can stop studying (and maybe show somebody else how to do it). Your practice is a process that began long before you encountered it, and will continue after you die. The goal is to never stop.

The successful student is not one who, having “succeeded” in “getting it,” stops. The successful student is one who never stops.

My friend and I, in our talk, settled on “space holder” and “jester” as maybe better models than “teacher.” Maybe “bullshitter” is better than “jester.” Skillful means and all that.

But the fact is that people, without being forced or seduced, gather together, and practice, and encourage each other in their practice, and awaken together. This process is inherent in human social reality, and has been going on for thousands of years, at least, and will continue.

What people need, to support that process, is spaces. Physical spaces, and that other, more subtle thing we mean when we say “space holder.”

What people need is hospitality.

I think there might be something of interest here for those who feel called to “teach” or help others. Rather than “teaching,” like a professor with a chalkboard, what if you were hosting? Making space, holding space, keeping people warm and fed and hydrated and safe; is that not a better model for how spiritual practice is encouraged, deepened, and developed?

༺ 𐂂 ༻

In the Provisional Manual of West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druidry (which you can buy and read — https://smallfires.cc/store), I listed four roles I had noticed in psychedelic circles and meditation halls: the Space Holder, the Fire Keeper, the Water Bearer, the Door Watch. In an act of total arbitrary poetry, I assigned them to the four directions: Space Holder in the North, Fire Keeper in the South, Water Bearer in the West, Door Watch in the East. To me, the axial directions seem more solemn and otherworldly, the rotational directions more goofy and interactive. The Space Holder’s awareness fills the room and goes beyond; the Fire Keeper attends to a presence that is not human. The Water Bearer (also cook and server; in our circles, for reasons lost in the mists of time, we call this person Franz the Psychedelic Butler) visits participants where they are and helps them with their needs; the Door Watch keeps track of comings and goings and keeps time.

In a zendo you can find these same four. The roshi, mentioned above, performs rituals and, well, holds space. The tanto or “head of practice” maintains the vibe. The tenzo, cook (and serving crew, if there are enough participants), makes the meals and serves them — this position is one of honor. There are many Zen stories in which cooks have the last word, and one of Dōgen’s most famous texts is the tenzokyokun, “Instructions for the Cook.” And the ino sits at the door and watches like a hawk. The ino is also in charge of the doanryo, who ring the bells and light the incense; but in a small zendo the ino does all these jobs.

They turn up, also, at dance parties. The DJ is ultimately responsible for holding space. But the sound person manages the more than human force that fills the space. The tea crew are there, all night long, making conversation, pouring tea, and helping people who may be having a difficult time. And the door crew keep everyone safe and enforce the rules. It would be weird, a total buzzkill, if the DJ got on the mic and started telling people what to do; and when the tea bros fuck with the soundboard, things go sideways. Principle in there.

Anyway this is all just one way of dividing it up. My point is that building, maintaining, and heating physical spaces for communities to discover and deepen their practice together — designing, facilitating, and vibecrafting events that take place within those spaces — and feeding, keeping safe and goofing around with the participants — all these are, I think, better ways to understand the roles of “senior students.” As I said in the thread at the beginning, we need way fewer bad teachers, and way more good students — and the best students are those that are hospitable to each other.

Genealogy of a Remix: Sickick’s GOMD

“Art criticizes society merely by existing.”

-Adorno

1.

Sickick’s track “GOMD” is theoretically a remix of a J Cole track of the same name. The metadata vary; on some sites it is listed as “GOMD by J Cole (Sickick Mix),” on others the artist name is just Sickick; on others it is “Sickick (J Cole).”

Both songs are driven by an eerie looped vocal sample; in the original it is loping, lopsided, vaguely like a fieldhand’s work song — in the Sickick version it has been edited to make it more rhythmic, sounding more like a gospel song, and an overdubbed lyric makes it seem to say

“me oh my, I’m a ghost, yo; me oh my, I’m a ghost.”

But that is not what it says.

J Cole, who is credited as producer of the original track, got the sample by chopping up two sections of a song on a Branford Marsalis album, editing them together and speeding them up so the male vocals of the original sound female.

But that song — “Berta, Berta” — is not by Marsalis. Marsalis doesn’t even play on it. The song is a chaingang shanty sung by enslaved railroad workers; and we know it because it was recorded at Parchman Farm in the 40s by Alan Lomax, the legendary collector of American folk music. The Marsalis version is a lot like Lomax’s original, but better-sounding — as it should be, since it was recorded in a studio; it is a kind of cinema verité re-creation, complete with loud katydid sound effects, swinging hammers, and a panting chorus, conducted for Marsalis by a musicologist called Dwight Andrews.

“Berta, Berta” is a tortured love song. In it a man, imprisoned at Parchman Farm, encourages his woman, on the outside, to leave him and marry someone else. We might pause for a moment to consider how it felt, for the men Lomax recorded, who were actually incarcerated at Parchman, to sing this song. Did they have women waiting for them on the outside? What did they make of this white guy and his microphone?

Anyway, the fragment edited and looped by J Cole, and re-edited by Sickick, says: “I might not want you, when I go free, oh ah.”

I don’t think either Cole or Sickick necessarily knew that; it’s kind of hard to make out the words. But listen closely and you will hear.

“I might not want you, when I go free.”

Now, Cole’s song is some frankly mid rapping about guns in the trunk and hoes with testicles in their mouth, unremarkable except for that chopped up sample. “GOMD” stands for “get off my dick.” All in all, it is an uninteresting example of 2010s commercial hiphop, not gangsta enough to be gangsta nor conscious enough to be conscious. But the video; we have to talk about the video a bit.

The video tells a story, a story completely unrelated to the lyrics which Cole mouths at the camera. In the video narrative Cole, an enslaved house servant on a plantation, unloved by the enslaved female house servants and disrespected by the enslaved field hands, steals the keys to the plantation gun cabinet and distributes the guns, starting an uprising, after which all the other enslaved servants smile at him with love and friendship.

There are a few different ways of looking at this narrative. Sympathetically, it is a call for those who find themselves in positions of access to use that access to advance the cause of collective liberation. You could also see it as some elitist revolutionary vanguard type shit; or even as wish-fulfillment LARPing. Whatever; what’s fascinating is that the narrative is so completely disconnected to anything about the song.

Except that vocal loop.

Cole reportedly had tried to use this narrative for a video to an earlier song; but is it not obvious? It is the sample, shining through, like a grave rubbing, that wanted a different story to be told. The anonymous singers on Lomax’s recording, refracted through Marsalis’s reimagining and Cole’s sample editing, are still haunting the ruined halls of popular music, ghostlike, revenants.

“Might not want you, when I go free.”

2.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, in Negative Dialectics, famously dissected what they called “the culture industry.” In the culture industry, what were originally spontaneous outpourings of human creativity become commodities, for sale at the price the market determines, a certain supply and a certain demand, fungible with one another; two cheap songs for one more expensive song.

In their working notes, they used the phrase “mass culture” instead of “culture industry,” but thought better of it; because the masses don’t produce the culture. The masses are produced by the culture. That is the industry. The culture industry makes humans into masses. Humans also become fungible; they are transformed from subjects of culture to its objects, consumers.

According to Teddy and Max, the former divisions between “high” and “low” art become drained of meaning by the culture industry. “High” art is no longer the precious cargo of generations of human experience, preserving lessons learned for the future; “low” art is no longer inherently rebellious and critical of the status quo. Rather, they become nothing more than two types of product intended for different segments of the population — ultimately no more different than Coke and Pepsi.

“Something is provided for all so that none may escape.”

Frederic Jameson, expanding on this, influentially defined postmodernism as an ahistoric condition, in which the history of culture exists only as pastiche, “speech in a dead language.” In place of history, of memory, there are only caricatures, period costumes, synthetic fakes. There is neither continuation, nor any real encounter with the reality of history or of culture; merely endless remixing of shallow references.

I agree with all these critiques; and yet there are other forces at play. I am not speaking of “remix culture” per se — most theorizing of remix culture remains unaware of Jameson’s profoundly pessimistic analysis, and so naïvely celebrates the “realm of the lost original,” the “free-floating signifiers,” and all the rest of it. These technical and economically predetermined elements of contemporary culture are, in a cynical view, only so many ways of saying “pastiche”; value-engineering, bad wine in good bottles, the tyranny of the same.

But I want to suggest that cultural currents swell and flow, beneath the surface of technocapitalism and its imperatives, following their own dark pathways. That what is repressed can return; that remix culture is also palimpsest culture, and that far from being an ahistoric schizophrenic collage of fakery, its history, its genealogy, is on display within it, is live and potent — as William Morris memorably put it, in a very different context:

“The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.”

3.

Along with the overwhelming majority of J Cole’s beats, Sickick discards his bars. Instead, his chopped and screwed, detuned voice raps in a horrorcore style:

“They call me the freak of the fall / Fuck a little bitch, I've come to take it all / I'm a ghost, who the fuck you gon' call? / Mossin’ with a scarecrow in the field, no (caw) / Lucifer reborn as a God / Feast on the blood drippin' down my jaw / Step out of my line and get outlined in chalk / Prince of the dark and the dead will walk”

Credits are hard to find for Sickick tracks. Information in general about him is hard to find, probably a tactical move by his handlers; he is one of those artists who only appears masked, a schtick that may have been cool when Doom did it, and works for Orville Peck I guess, but unfortunately risks falling into Deadmau5-style cringe all too easily. My wife, a dj, tells me his name is pronounced “psychic,” though I’m not sure how she knows that. Anyway, no other vocalists are mentioned anywhere in connection with this track; which either means that the woman’s voice that sings the next verse is uncredited or, I suspect, is also Sickick, pitch-shifted up this time:

“I can feel my enemy begin to fear my drum / I am ready, when it comes to pain I'm numb / I could tell you things you won't believe I've done / I kill to feel alive”

And then, carrying the song to the end of its brief two minutes and ten seconds:

“Me oh my, I’m, a ghost, yo / Me oh my, I’m, a ghost”

It would be the crudest kind of pretension to intellectually analyze these lyrics, which do not work on that level at all. But we have to ask: Who is the ghost? Whose ghost?

How did a ghost come to be speaking here? How was it given voice? What is it trying to say?

Sickick retains only one thing from J Cole’s track; a vocal loop, which he re-edits to make it more percussive, more insistent.

And as the song ends, Sickick, a man, sings in a woman’s voice lyrics which sound like, but are not, the vocals sampled by another artist, detuned to sound like women’s voices, though they are men’s voices, reproducing other men’s voices from a yet earlier recording.

Incarcerated men, singing a work song to make their forced labor bearable. Their voices, like ghosts, haunting the airwaves; moving across the decades with their own agenda. Ghost voices announcing themselves insistently, refusing to be silenced.

16 March 2025

Touch Fucking Moonflower

A Toast for this Mayday 2024

So, two years ago I gave a toast at our May Eve Dinner, — some of you were there — at our former home, Moonflower Farm — where among many other erudite references I quoted Plutarch claiming that at Delphi, which was mostly a temple of Apollo, they also worshipped Dionysus, but only for three months of the year, and that this was because the ratio of the world’s maintenance to its destruction by fire is 3:1. I thought I was making a poetic reference to my mother’s cremation, which had recently transpired — but a little over a month after I proposed that toast, a wildfire had burned our home and all our possessions.

So last year I was afraid to give a toast.

But, this year, throwing caution to the winds:

I was thinking about how some of us will be sleeping “under the stars” this weekend — and how actually we all are. Actually we will all sleep under the stars tonight, both under them and over them, and in between them — tucked in.

I was thinking about how some friends of mine are excited to send humans out into space — as if we’re not already in space. As if the Earth, and all of us on it, were not already hurtling through space. Some 70,000 mph relative to the Sun — but then if you think about it, the Sun is also moving. The Sun — and the Earth with it — are traveling some 500,000 mph relative to the center of the galaxy. And the galaxy itself — well.

So, the Earth may be hurtling; or I guess from another perspective it’s just drifting. It depends on what they call the “inertial frame”. But in any case, it is most certainly moving through space, and there is no doubt that humanity is already, and have always been, from our earliest ancestors, spacefarers.

As I was thinking about all of this, I came across in an old book the remarkable analogy that if you emptied Waterloo Station — which is an enormous building in London — of everything but six specks of dust, if you took out all the people, all the trains, all the furniture, the sandwich carts, and all that was left was six tiny specks of dust — it would still be more crowded, with dust, than space is with stars.

The emptiness all around us is truly vast.

This of course brought to my mind the story that Alan Watts told from time to time — which as far as I can tell he made up, there’s no record of it anywhere outside his lectures — of an astronaut, returning to Earth who said: “I have seen God; and She is black.”

All of which made me think of the seventeenth century French Benedictine Friar Pierre Pérignon — who is remembered by the traditional honorific “Dom”, Dom Pérignon — a monastic at an abbey in the Champagne region of France — who was inspecting some of the abbey’s wine, which had begun to referment in the bottle, and was in danger of exploding, and is supposed to have called out, “Brothers, brothers, come quickly! I am drinking stars!”

And so. Sisters! Brothers! Come quickly. Stars above us, stars below us; stars outside us, stars within; we hurtle, we drift, through the vast emptiness of space; together.

Moonflower Farm Occasional Dispatches Seven: A Dithyramb for this Mayday 2022

Plutarch — in a text called “On the ει at Delphi” — reports that Apollo, the deity moderns associate with Delphi, was not the only one worshiped there, but shared the temple with an older occupant, Dionysus — Apollo being worshiped nine months of the year and Dionysus three. Plutarch observes that while Apollo is always depicted the same way, as a virile young man in the prime of life, Dionysus is represented in a huge variety of forms: a young man, an old man; a bull, a snake, a thunderbolt; a flowering bush, a grapevine; in infancy, in death. And very often, in some combination of those two conditions, for just as the archaic form of Dionysus, Zagreus, was torn from his mother’s womb and dismembered by the Titans, and his still beating heart was cradled in his father Zeus’s thigh — they say “thigh”, but everybody knows it means balls, Zeus kept his son’s heart in his balls for nine months of gestation, until he burst forth in a second birth — which is why (they say) songs in praise of Dionysus are called dithyrambs, “songs of the double door”. Just so in Euripides’ Bacchae Pentheus, arch-rationalist ruler and denier of holy madness, dresses in drag in order to spy on the rites — and we recall that in the immortal words of Ru Paul, we are born naked and we die naked, and all the rest is drag — and is torn asunder by his own wife and mother, who mistake him for a wild beast — or so they say anyway. And indeed Orpheus, variously seen as avatar, enemy, and prophet of Dionysus, having lost Eurydice to the underworld by his backward-glancing lack of faith, was unable to shut up about it until maenads tore him in turn and scattered the pieces; in his case it was the head, not the heart that was preserved, even in death singing on the waters, a song we can hear to this day in the humming of bees. Dionysus thus is somehow a divinity who is incarnated in those who deny his divinity — though this incarnation is their doom (and ours?).

Anyway, Plutarch explains that Dionysus is worshiped for three months of the year to Apollo’s nine because the ratio of the ordering of the world to its conflagration is held by the Delphic priests to be three to one.

So, that’s what I’ve been thinking about this Spring; ordering and conflagration, hearts and heads, birth and death and drag; my mother died a few months ago, my wife will soon be pregnant; and I’d like us all to raise a glass in the words of Dylan Thomas, to “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower drives [our] green age”.

Moonflower Farm Occasional Dispatches 5: The Mother of All Sorrows

Moments from the First West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druid Funeral, together with Various Observations on Technocapitalist Death Practices, and Some Notes on Grief

First Day

My mother died, aged 96, in 2022, Late Winter, 2º Lunation, Waning Crescent Moon, on Tuesday 25 January at 8:24 am. Actually she probably died earlier than that; the precision of the time of death is an artifact of bureaucracy. Staff at her care home were supposedly checking on her every hour, and at some point that morning someone noticed she wasn’t breathing and called the hospice nurse to come pronounce her dead — I think the time recorded by hospice on her death certificate is the time they were notified. Hospice is required by law to inform a funeral home, and I had requested that they tell the funeral home not to come immediately, as we wanted some time with the body first.

Originally, when Mom had been living with us, we had arranged to have her body stay with us after death. I had never discussed this with the care home, so when it became clear she was dying, I asked if we could hold vigil with her body in her room there, expecting them to say no; usually such places have a policy that bodies must be removed within hours. To my pleasant surprise the director replied immediately that while no one had ever requested this before, she had no problem with it, and offered to assist in any way possible.

However, a week or so before Mom died, she had a difficult night, tumbling out of the hospital bed they had insisted on installing, breaking her side table, and badly scraping her shins and forearms. Some kind of arcane bureaucratic rule prohibits residential care homes from treating open wounds beyond a certain “stage”, which is determined by a hospice nurse, and likewise prohibits insurance from paying hospice for the care of those wounds; the upshot was that a social worker called to inform me that Mom would have to be moved to a skilled nursing facility, at first nicely, and, when I balked, insistently, eventually threatening me with taking the decision out of my hands by calling Adult Protective Services, a government agency.

For those who may not know, “Skilled Nursing Facilities” are depressing and very profitable warehouses for old people which proliferate across the suburban landscape, usually converted schools, nunneries or other institutions. The usual end-of-life trajectory in America, which I had already avoided several times for my mother, is that an elder suffers an injury, is sent to a hospital, and then moved to a SNF (pronounced “sniff”) for “rehabilitation”. SNFs are, of course, breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant pneumonias, so most contemporary Americans die of morphine administered to keep them “comfortable” while afflicted by pneumonia subsequent to a broken bone or soft tissue injury.

This is what Arendt memorably described as the banality of evil.

However, unpleasant as this all was, it got us to thinking: If Mom was doomed to die in a SNF, they were most certainly not going to allow her body to remain, which meant our only option for holding vigil with her body would be to somehow transport it to our home, in the middle of nowhere at the end of miles of gravel and dirt roads, in a dirt-floored building with neither electricity nor running water. The end-of-life doula we were working with had never encountered such a situation, but said there was nothing we could do but ask. So I did; after several unanswered messages eventually contacting someone at the funeral parlor who, just like the care home, said that while no one had ever requested this before, she didn’t see why it couldn’t be done. They charge a flat fee for transporting a body from the place of death to the crematorium, and they just agreed to bill me twice, once for transport to our property and once for transport from it.

So it was that my wife and I found ourselves driving into town to meet two end-of-life doulas, along with two dear friends, one with her teen child in tow, at Mom’s care home apartment, a hastily-scrawled “Do Not Disturb” sign taped to the locked door.

Death is a funny old thing (as is life). Mom’s head and hands were cold and stiff; her neck and back were still warm and supple. The doula asked if I would like a moment. I leaned over and held my mother’s dear head in my arms and burst into breathless hysterical sobs. Once I was able to speak, all I could say was “Thank you”, over and over, overwhelmed by unutterable gratitude for the mystery of my own existence. When I looked up, I saw the doula had kneeled, head bowed, behind me.

Eventually I got myself together and we began to organize things. Two basins filled with water, one with essential oils added (we had chosen frankincense, clary sage, and myrrh) and a second for rinsing; a stack of washcloths; diapers; wipes. It turns out that much of the lost art of preparing a body for a wake has to do with the fact that, upon death, various sphincter muscles lose their tone and the intestine and bladder their contents.

Mom’s bladder kept leaking small amounts of pee and we kept having to change her diapers and wipe her clean again. Here, I was grateful for the doulas’ presence. Over the weeks prior, as Mom had spent more and more time sleeping and become harder and harder to rouse, I had come to see her as less “person” and more “body”. I was especially fortunate to have been sitting with her a few nights previous when the night hospice nurse, a very nice, capable, and eccentric ex-hippie named Anne, came to change the dressings on her bedsores. Anne was alone, so together we rolled Mom from one side to another, and my desperate sense of helplessness in the face of her frail old form abated somewhat. Still, wiping her nether regions would have been hard. I was able to hold one leg in the air a bit to help.

As each friend arrived I could see them go through some of the same process; from shock, to embarrassment and mild disgust, to compassionate practical assessment of the job at hand. We washed her face, her feet, her hands and arms; between her toes, her body’s creases and wrinkles. Eventually it was time to dress her. My wife had chosen a beautiful black kaftan, which my ex had brought Mom back from the middle east, and in which Mom had always looked especially elegant; in recent years she had taken to wearing it, with a witch’s hat, at Halloween. Mom’s first halloween at the care home she actually won the prize for best costume and you would think she had won a Macarthur Fellowship — her innocent pride was so sweet and comical — for weeks afterward she kept saying, “I can’t believe it! I’ve never won anything in my life!”

Anyway eventually the doula suggested we just slit it down the back in order to get it on, as Mom was going to be supine from then on, and the garment was to go with her into the flames anyway. At first it proved difficult to wrestle her arms into the sleeves, as they had gotten quite stiff (especially the left one), but after massaging them for a few minutes they became more flexible again: Another of the lost arts of care for the dead.

For of course, it is only very very recently that our society has forgotten what death is and how to handle it. Death in hospitals (and more recently, SNFs) only became common in the 1940s, and is unknown in most of the world even today. Only a few short centuries ago, every adult would have been around occasional dead people starting in childhood, and how to wash a dead body would have been common knowledge in much the same way as how to wash a live one.

Interestingly, Mom’s left arm rather quickly returned to its original bent position and stiffened up again. Her right eye, too — when we arrived it was open, as was her mouth. Often, in the hours immediately after death, mouths are tied shut for decorum, so they stiffen that way. We decided not to do that with Mom, as her mouth was in more or less the position it had been for several days as she slept. But her eye, gleaming there, was a little unsettling. I sort of liked that and a couple of times when I found it closed, I pulled the lid open again; eventually my wife saw me doing it and laughed, saying she had been closing it, to make Mom less scary. In any case, the eye seemed to have a mind of its own; and in the event, as it became duller over the next few days, it stopped being so noticeable.

The timing was just right, as Mom was dressed when our friend with her teen child arrived. I think hanging out in a room with a dead body was probably squiggy enough for them — a naked old lady dead body probably would have been too much. The teen’s mother had, among many things, been Mom’s hairdresser off and on over the years and she cried softly while brushing and arranging Mom’s hair, spreading scarves to hide the bandages on Mom’s arms. My wife trimmed the hairs on Mom’s chin, something she had also sometimes done in life.

The manager of the funeral home was also driving the van that day, many of the employees being out sick with covid; the care home instructed her to bring her gurney in through the “cupcake room”. It was the first time I had heard about the “cupcake room” but apparently it also serves as a secret final exit from the care home; of course it would be bad for business to remind the other residents too viscerally of the manner in which their residency will most certainly come to an end.

So, the funeral home van, our friends, and we, snaked in single file along the increasingly narrow and windy mountain roads to Moonflower Mahasangha. I can only assume it all seemed increasingly weird to them; but they gave no sign, calmly and professionally wheeling Mom’s gurney onto the raw dirt floor and transferring her onto the bed beneath the huge skylight of our Big House. Once the job was done, they exclaimed over the beauty of the building (which is, indeed, very beautiful) and took their leave. No papers were signed, no money changed hands; they merely instructed us to call when we were ready. No liability waivers, no transfer of responsibility, no safety inspection — they just left us alone with my mother’s corpse.

Over the next three days, I asked several people who seemed like they might know, “What happens if I never call to have her picked up?” Other than baffled affirmations of its impossibility, I received no satisfactory answers. Home cremation, home burial, are undoubtedly against the law, certainly without mountains of paperwork — but exactly how those laws are enforced, it appears no one knows. The very idea is simply so beyond the pale that what cannot be thought does not need to be enforced. There is a principle in here which West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druids should take to heart, and this area is clearly ripe for further research.

The doulas had procured dry ice and some ice packs on the way; we put them under the body beneath the lumbar, thoracic and cervical spine areas. The dry ice worked great and lasted, in Winter, for about 24 hours — you have to wear leather gloves and break it with a hammer, and wrap it in heavy brown paper — but one could certainly use ice packs, frozen peas, or any such thing. The principle is simply to chill the digestive areas and the brain, and keep them cold; the doula also emphasized wrapping the ice packs in cloth, to avoid condensation. Each night she instructed us to place another ice pack on Mom’s belly.

We cut some large branches of manzanita and sprigs of rosemary and surrounded Mom with these along with cut flowers and peacock feathers. Mom had (still has as of this writing, her cremation won’t take place for several weeks) a tattoo of a peacock feather on her left shoulder which she got around age 65. Her love of peacocks originated with a medieval recipe she found somewhere titled “To Roast a Peacocke with All His Feathers”, a very elaborate preparation which includes lighting camphor in the bird’s beak so it appears to be spitting fire, which delighted Mom so much she ended up making eight or ten one-of-a-kind illustrated calligraphic hand-bound books of it, each more elaborate and surreal than the last and you know, it is really only as I write this that I am coming to understand how delightful, irreverent and eccentric she was; it is difficult, maybe impossible, to really see the people we love, to really understand what it is we love about them, until they are no longer here. Strange.

Mom after she got her tattoo

Surrounded thus, with candles lit, Tibetan prayer beads twined in her fingers and a radiant chunk of amber around her neck, her white hair loose and flowing over her shoulders, Mom looked like what she was, what she is now: A Baltic warrior witch queen, even stronger and more beautiful in death than she had ever been in life, perhaps in some sense more fully herself than she had ever been in life. Anyway that is how it seemed to me. It seemed, when the arrangement was complete, that that she had been, herself, transformed into a work of art, that her death had been transformed into a work of art, that her death might be her last and greatest work of art — may all our deaths be thus.

Second Day

Several friends came to visit and sit with Mom. Having people around was a godsend, but if I had it all to do over again I would curtail my instinct to play host. By the afternoon, after a full day of alternately grieving and interacting, I was so drained I wasn’t sure whether I was going to need cremation too.

An observation, on this and subsequent days, was that my attitude to the whole ritual was pretty laissez-faire — I basically felt that there was a dead body around and people should take advantage of the opportunity to freak themselves out. My friends, of course, were there for me (or possibly even for Mom?), and were looking to me for guidance on what to do and when. I am pretty good at holding space, but am often reluctant to lead other than by example, which is probably a fatal flaw. So be it.

When everyone had gone, I had soaked in a bath for an hour, and my wife and I had dined, I put on warm clothes and opened a beer and walked the quarter mile back to the Big House. Frogs were singing loudly as they do this time of year; the Moon was still a sliver and too near the Sun to be seen. I entered Mom’s space with the resigned trepidation that I have felt many times going back down to the Zendo at night when everyone has gone to bed, or walking to the Maloca to drink ayahuasca — the sense of crossing over, of leaving normal life behind and embarking on a journey into nowhere.

That night, I sat with her quietly, occasionally weeping; eventually I sat on the bed with her, hugging her and kissing her ice cold forehead and cheeks, crying until snot and tears dripped on her face. During her final weeks, I had kissed her forehead in just this way so many times, hoping that some sense of my love would reach her, and offer her some comfort in the dreamy delirium in which she was wandering. I held her cold stiff hand, sobbing, begging her to squeeze my hand back as she often had a week or two before; but she did not.

I began then to ask Mom some questions. I asked her why she never remarried after my Dad died — she told me that when you love someone like that, no other love can measure up. I think she was not being completely frank, but that is what she said.

I asked about the scars on her thighs. Mom had (again, still presumably has as of this writing) terrible scars on her upper thighs, visible to anyone who helped her dress. Once, when I was 10 or so I suppose — maybe younger? — and she did not know I was there, I saw her break a glass on the floor, then hike her skirt up and slash angrily at her thigh. She said something to me about it when she realized I had seen, I am not sure what, the memory is a little vague — but we never spoke about it again, ever, for nigh on 50 years. I do not know how well she remembered that time in her life, whether she thought about it. It was a dark time, a difficult time for me and obviously for her; it was mostly pretty awkward to talk about, and we didn’t. But that night I asked her about it, stammering, trying to find the words. And I received an answer, in the way you learn things sometimes when tripping, or alone in the mountains, or sitting zazen.

I sat with Mom a long time that night — I do not know how long. I turned the electric candles off and sat with her in the dark. Eventually I put an ice pack on her stomach, walked back down the path to our cottage, and crawled into bed with my sweetie. She felt so strange. Her warmth, suppleness, her beating heart and pumping lungs and dewy skin, all felt wrong somehow.

For I had been to a land where everything and everyone is cold and stiff and dry and unmoving. I had become acclimatized to death, to the land of death, dim and shadowy, still and sad. It took me a while to come back, and at first I didn’t really want to.

One of the strange things I have noticed about being with dead bodies is that they seem to breathe. I always think I see their chests rising and falling — and then look again and realize they are not. I think we are deeply unconsciously aware of each other’s breath, that we are monitoring it or resting on it or interpenetrating with it all the time, and one of the things that makes dead bodies so unnerving is their breathlessness.

Third Day