Moonflower Farm Occasional Dispatches 5: The Mother of All Sorrows

Moments from the First West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druid Funeral, together with Various Observations on Technocapitalist Death Practices, and Some Notes on Grief

First Day

My mother died, aged 96, in 2022, Late Winter, 2º Lunation, Waning Crescent Moon, on Tuesday 25 January at 8:24 am. Actually she probably died earlier than that; the precision of the time of death is an artifact of bureaucracy. Staff at her care home were supposedly checking on her every hour, and at some point that morning someone noticed she wasn’t breathing and called the hospice nurse to come pronounce her dead — I think the time recorded by hospice on her death certificate is the time they were notified. Hospice is required by law to inform a funeral home, and I had requested that they tell the funeral home not to come immediately, as we wanted some time with the body first.

Originally, when Mom had been living with us, we had arranged to have her body stay with us after death. I had never discussed this with the care home, so when it became clear she was dying, I asked if we could hold vigil with her body in her room there, expecting them to say no; usually such places have a policy that bodies must be removed within hours. To my pleasant surprise the director replied immediately that while no one had ever requested this before, she had no problem with it, and offered to assist in any way possible.

However, a week or so before Mom died, she had a difficult night, tumbling out of the hospital bed they had insisted on installing, breaking her side table, and badly scraping her shins and forearms. Some kind of arcane bureaucratic rule prohibits residential care homes from treating open wounds beyond a certain “stage”, which is determined by a hospice nurse, and likewise prohibits insurance from paying hospice for the care of those wounds; the upshot was that a social worker called to inform me that Mom would have to be moved to a skilled nursing facility, at first nicely, and, when I balked, insistently, eventually threatening me with taking the decision out of my hands by calling Adult Protective Services, a government agency.

For those who may not know, “Skilled Nursing Facilities” are depressing and very profitable warehouses for old people which proliferate across the suburban landscape, usually converted schools, nunneries or other institutions. The usual end-of-life trajectory in America, which I had already avoided several times for my mother, is that an elder suffers an injury, is sent to a hospital, and then moved to a SNF (pronounced “sniff”) for “rehabilitation”. SNFs are, of course, breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant pneumonias, so most contemporary Americans die of morphine administered to keep them “comfortable” while afflicted by pneumonia subsequent to a broken bone or soft tissue injury.

This is what Arendt memorably described as the banality of evil.

However, unpleasant as this all was, it got us to thinking: If Mom was doomed to die in a SNF, they were most certainly not going to allow her body to remain, which meant our only option for holding vigil with her body would be to somehow transport it to our home, in the middle of nowhere at the end of miles of gravel and dirt roads, in a dirt-floored building with neither electricity nor running water. The end-of-life doula we were working with had never encountered such a situation, but said there was nothing we could do but ask. So I did; after several unanswered messages eventually contacting someone at the funeral parlor who, just like the care home, said that while no one had ever requested this before, she didn’t see why it couldn’t be done. They charge a flat fee for transporting a body from the place of death to the crematorium, and they just agreed to bill me twice, once for transport to our property and once for transport from it.

So it was that my wife and I found ourselves driving into town to meet two end-of-life doulas, along with two dear friends, one with her teen child in tow, at Mom’s care home apartment, a hastily-scrawled “Do Not Disturb” sign taped to the locked door.

Death is a funny old thing (as is life). Mom’s head and hands were cold and stiff; her neck and back were still warm and supple. The doula asked if I would like a moment. I leaned over and held my mother’s dear head in my arms and burst into breathless hysterical sobs. Once I was able to speak, all I could say was “Thank you”, over and over, overwhelmed by unutterable gratitude for the mystery of my own existence. When I looked up, I saw the doula had kneeled, head bowed, behind me.

Eventually I got myself together and we began to organize things. Two basins filled with water, one with essential oils added (we had chosen frankincense, clary sage, and myrrh) and a second for rinsing; a stack of washcloths; diapers; wipes. It turns out that much of the lost art of preparing a body for a wake has to do with the fact that, upon death, various sphincter muscles lose their tone and the intestine and bladder their contents.

Mom’s bladder kept leaking small amounts of pee and we kept having to change her diapers and wipe her clean again. Here, I was grateful for the doulas’ presence. Over the weeks prior, as Mom had spent more and more time sleeping and become harder and harder to rouse, I had come to see her as less “person” and more “body”. I was especially fortunate to have been sitting with her a few nights previous when the night hospice nurse, a very nice, capable, and eccentric ex-hippie named Anne, came to change the dressings on her bedsores. Anne was alone, so together we rolled Mom from one side to another, and my desperate sense of helplessness in the face of her frail old form abated somewhat. Still, wiping her nether regions would have been hard. I was able to hold one leg in the air a bit to help.

As each friend arrived I could see them go through some of the same process; from shock, to embarrassment and mild disgust, to compassionate practical assessment of the job at hand. We washed her face, her feet, her hands and arms; between her toes, her body’s creases and wrinkles. Eventually it was time to dress her. My wife had chosen a beautiful black kaftan, which my ex had brought Mom back from the middle east, and in which Mom had always looked especially elegant; in recent years she had taken to wearing it, with a witch’s hat, at Halloween. Mom’s first halloween at the care home she actually won the prize for best costume and you would think she had won a Macarthur Fellowship — her innocent pride was so sweet and comical — for weeks afterward she kept saying, “I can’t believe it! I’ve never won anything in my life!”

Anyway eventually the doula suggested we just slit it down the back in order to get it on, as Mom was going to be supine from then on, and the garment was to go with her into the flames anyway. At first it proved difficult to wrestle her arms into the sleeves, as they had gotten quite stiff (especially the left one), but after massaging them for a few minutes they became more flexible again: Another of the lost arts of care for the dead.

For of course, it is only very very recently that our society has forgotten what death is and how to handle it. Death in hospitals (and more recently, SNFs) only became common in the 1940s, and is unknown in most of the world even today. Only a few short centuries ago, every adult would have been around occasional dead people starting in childhood, and how to wash a dead body would have been common knowledge in much the same way as how to wash a live one.

Interestingly, Mom’s left arm rather quickly returned to its original bent position and stiffened up again. Her right eye, too — when we arrived it was open, as was her mouth. Often, in the hours immediately after death, mouths are tied shut for decorum, so they stiffen that way. We decided not to do that with Mom, as her mouth was in more or less the position it had been for several days as she slept. But her eye, gleaming there, was a little unsettling. I sort of liked that and a couple of times when I found it closed, I pulled the lid open again; eventually my wife saw me doing it and laughed, saying she had been closing it, to make Mom less scary. In any case, the eye seemed to have a mind of its own; and in the event, as it became duller over the next few days, it stopped being so noticeable.

The timing was just right, as Mom was dressed when our friend with her teen child arrived. I think hanging out in a room with a dead body was probably squiggy enough for them — a naked old lady dead body probably would have been too much. The teen’s mother had, among many things, been Mom’s hairdresser off and on over the years and she cried softly while brushing and arranging Mom’s hair, spreading scarves to hide the bandages on Mom’s arms. My wife trimmed the hairs on Mom’s chin, something she had also sometimes done in life.

The manager of the funeral home was also driving the van that day, many of the employees being out sick with covid; the care home instructed her to bring her gurney in through the “cupcake room”. It was the first time I had heard about the “cupcake room” but apparently it also serves as a secret final exit from the care home; of course it would be bad for business to remind the other residents too viscerally of the manner in which their residency will most certainly come to an end.

So, the funeral home van, our friends, and we, snaked in single file along the increasingly narrow and windy mountain roads to Moonflower Mahasangha. I can only assume it all seemed increasingly weird to them; but they gave no sign, calmly and professionally wheeling Mom’s gurney onto the raw dirt floor and transferring her onto the bed beneath the huge skylight of our Big House. Once the job was done, they exclaimed over the beauty of the building (which is, indeed, very beautiful) and took their leave. No papers were signed, no money changed hands; they merely instructed us to call when we were ready. No liability waivers, no transfer of responsibility, no safety inspection — they just left us alone with my mother’s corpse.

Over the next three days, I asked several people who seemed like they might know, “What happens if I never call to have her picked up?” Other than baffled affirmations of its impossibility, I received no satisfactory answers. Home cremation, home burial, are undoubtedly against the law, certainly without mountains of paperwork — but exactly how those laws are enforced, it appears no one knows. The very idea is simply so beyond the pale that what cannot be thought does not need to be enforced. There is a principle in here which West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druids should take to heart, and this area is clearly ripe for further research.

The doulas had procured dry ice and some ice packs on the way; we put them under the body beneath the lumbar, thoracic and cervical spine areas. The dry ice worked great and lasted, in Winter, for about 24 hours — you have to wear leather gloves and break it with a hammer, and wrap it in heavy brown paper — but one could certainly use ice packs, frozen peas, or any such thing. The principle is simply to chill the digestive areas and the brain, and keep them cold; the doula also emphasized wrapping the ice packs in cloth, to avoid condensation. Each night she instructed us to place another ice pack on Mom’s belly.

We cut some large branches of manzanita and sprigs of rosemary and surrounded Mom with these along with cut flowers and peacock feathers. Mom had (still has as of this writing, her cremation won’t take place for several weeks) a tattoo of a peacock feather on her left shoulder which she got around age 65. Her love of peacocks originated with a medieval recipe she found somewhere titled “To Roast a Peacocke with All His Feathers”, a very elaborate preparation which includes lighting camphor in the bird’s beak so it appears to be spitting fire, which delighted Mom so much she ended up making eight or ten one-of-a-kind illustrated calligraphic hand-bound books of it, each more elaborate and surreal than the last and you know, it is really only as I write this that I am coming to understand how delightful, irreverent and eccentric she was; it is difficult, maybe impossible, to really see the people we love, to really understand what it is we love about them, until they are no longer here. Strange.

Mom after she got her tattoo

Surrounded thus, with candles lit, Tibetan prayer beads twined in her fingers and a radiant chunk of amber around her neck, her white hair loose and flowing over her shoulders, Mom looked like what she was, what she is now: A Baltic warrior witch queen, even stronger and more beautiful in death than she had ever been in life, perhaps in some sense more fully herself than she had ever been in life. Anyway that is how it seemed to me. It seemed, when the arrangement was complete, that that she had been, herself, transformed into a work of art, that her death had been transformed into a work of art, that her death might be her last and greatest work of art — may all our deaths be thus.

Second Day

Several friends came to visit and sit with Mom. Having people around was a godsend, but if I had it all to do over again I would curtail my instinct to play host. By the afternoon, after a full day of alternately grieving and interacting, I was so drained I wasn’t sure whether I was going to need cremation too.

An observation, on this and subsequent days, was that my attitude to the whole ritual was pretty laissez-faire — I basically felt that there was a dead body around and people should take advantage of the opportunity to freak themselves out. My friends, of course, were there for me (or possibly even for Mom?), and were looking to me for guidance on what to do and when. I am pretty good at holding space, but am often reluctant to lead other than by example, which is probably a fatal flaw. So be it.

When everyone had gone, I had soaked in a bath for an hour, and my wife and I had dined, I put on warm clothes and opened a beer and walked the quarter mile back to the Big House. Frogs were singing loudly as they do this time of year; the Moon was still a sliver and too near the Sun to be seen. I entered Mom’s space with the resigned trepidation that I have felt many times going back down to the Zendo at night when everyone has gone to bed, or walking to the Maloca to drink ayahuasca — the sense of crossing over, of leaving normal life behind and embarking on a journey into nowhere.

That night, I sat with her quietly, occasionally weeping; eventually I sat on the bed with her, hugging her and kissing her ice cold forehead and cheeks, crying until snot and tears dripped on her face. During her final weeks, I had kissed her forehead in just this way so many times, hoping that some sense of my love would reach her, and offer her some comfort in the dreamy delirium in which she was wandering. I held her cold stiff hand, sobbing, begging her to squeeze my hand back as she often had a week or two before; but she did not.

I began then to ask Mom some questions. I asked her why she never remarried after my Dad died — she told me that when you love someone like that, no other love can measure up. I think she was not being completely frank, but that is what she said.

I asked about the scars on her thighs. Mom had (again, still presumably has as of this writing) terrible scars on her upper thighs, visible to anyone who helped her dress. Once, when I was 10 or so I suppose — maybe younger? — and she did not know I was there, I saw her break a glass on the floor, then hike her skirt up and slash angrily at her thigh. She said something to me about it when she realized I had seen, I am not sure what, the memory is a little vague — but we never spoke about it again, ever, for nigh on 50 years. I do not know how well she remembered that time in her life, whether she thought about it. It was a dark time, a difficult time for me and obviously for her; it was mostly pretty awkward to talk about, and we didn’t. But that night I asked her about it, stammering, trying to find the words. And I received an answer, in the way you learn things sometimes when tripping, or alone in the mountains, or sitting zazen.

I sat with Mom a long time that night — I do not know how long. I turned the electric candles off and sat with her in the dark. Eventually I put an ice pack on her stomach, walked back down the path to our cottage, and crawled into bed with my sweetie. She felt so strange. Her warmth, suppleness, her beating heart and pumping lungs and dewy skin, all felt wrong somehow.

For I had been to a land where everything and everyone is cold and stiff and dry and unmoving. I had become acclimatized to death, to the land of death, dim and shadowy, still and sad. It took me a while to come back, and at first I didn’t really want to.

One of the strange things I have noticed about being with dead bodies is that they seem to breathe. I always think I see their chests rising and falling — and then look again and realize they are not. I think we are deeply unconsciously aware of each other’s breath, that we are monitoring it or resting on it or interpenetrating with it all the time, and one of the things that makes dead bodies so unnerving is their breathlessness.

Third Day

An old friend of Mom’s, mother of my nursery school besty, who now sits on a number of boards including that of a funeral industry consumer advocacy nonprofit, came to visit. She was great, brought us hands down the best almonds I have ever eaten, which she grew in her orchard and roasted herself — but the funny thing was that, while she advocates for the right to hold home funerals like ours, her discomfort with the actual presence of Mom’s body was palpable. She did not look at Mom, did not examine any of the ephemera we had gathered, just talked non-stop the entire time she was in the room. Only when getting in her car to leave did she acknowledge to me that she had never been to a home funeral before.

The moral here is that allies come in many varieties. Nine bows to her for working tirelessly on behalf of what she may not fully understand.

Several friends gathered that afternoon and evening to spend the night. Dear friends who drive for hours, clear their schedules, bring delicious food to share. Ride or die friends, who can be difficult as can all people when you come to know them well, and, when the rubber hits the road, are always there to help. Friends who saw, in my mother, what I could not see, because she was my mother: The possibility of growing old creatively.

This is the vision: That death be a community project, an opportunity to cut against the grain of technocapitalist atomization, to reconnect to the Earth and its all-embracing heartache.

We ate together, speaking happily of old times, polishing off a couple bottles of sparkling rosé, and then made our way to the Big House. One friend had brought a formal tea set, a bell, and some books of Buddhist sutras. We sat in meditation, circling Mom’s body, for 20 minutes or so. At one point he bumped into some cowbells hanging from a rafter and I observed, “There are bells of order, and bells of chaos.”

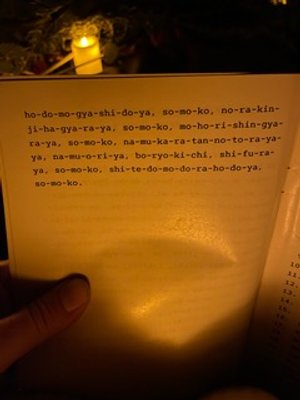

Our dear friend led us in chanting, intoning in a deep gruff Rinzai growl. We chanted the Heart Sutra in Sinojapanese and then a very old magic spell, chanted in the Chinese approximation of an older Sanskrit original, called the Daihi Shin Dharani, the Great Compassionate Mind Dharani; it is traditionally chanted in memoriam, and has been for two thousand years or so. Since we didn’t have a printout of the Heart Sutra in English, I recited as much as I could remember, so Mom could hear it, and so I could too. “Shariputra, form does not differ from emptiness, emptiness does not differ from form. Form itself is emptiness, emptiness itself form. Sensations, perceptions, formations and consciousness are also like this. Shariputra, all things are marked by emptiness; they neither arise nor cease, are neither defiled nor pure, neither increase nor decrease. Given emptiness, there is no form, no sensation, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no sight, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no realm of sight, no realm of mind consciousness; no suffering, no cause, no cessation, no path, no knowledge, and no attainment.”

Another friend had brought delicious homemade bourbon balls which we snacked on; and another marshmallows. Mom’s face had always lit up with childlike glee when she was offered a marshmallow.

That night we left the electric candles lit, and crawled into our respective beds around the property. Some slept in the Big House with Mom — I believe they all had a quiet night.

Fourth Day

I was anxious when I awoke. The death doula was texting, asking if I had made arrangements for pickup with the funeral home, which I hadn’t yet; I had to bustle around and find the forms they had left me and call my uncle to get some facts required for the death certificate. I say “facts”, but in the event my uncle and I just settled on likely answers, as neither one of us knew the real answers for sure. A friend observed that this is how history gets written: A couple of men sitting around and saying, well, that’s probably about right. And then it is filed with the government and signed in triplicate and lo and behold, it is the truth.

My wife and I put on nice clothes, not too formal, but we both looked very handsome. I was still feeling anxious so I fussed around the Big House, sweeping, getting music ready to be played. I put on Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, which is the music I would like played at my memorial; the bass’s ringing “Dunkel, ist das liebe, ist … der … tod (Dark is life, is death)” bringing the first tears of the day to my eyes.

By the time everyone had assembled — the death doula came too — the final section, Der Abschied, was playing, and I was crying uncontrollably, gasping “no, no” from time to time, almost unable to breathe. People read poems, someone read the passage from John Crowley’s Little, Big where the protagonist, Smoky, collapses with a heart attack and his life spirals around him, which brought yet more tears welling up. I read the English of the libretto of Der Abschied, “The Farewell”, but the words felt empty in my mouth. I read a poem to Mom written by my ex’s elder daughter, who had been close to Mom but hadn’t spoken to any of us in years and as I write this, I remember Mom explaining to me that you only use the superlative when there are three or more items in a collection and so if there are two daughters and five sons you say elder daughter but eldest son.

I remember her teaching me how to punch down bread dough after it has risen, how to roll out a pie crust; arguing with me about nuances of grammar; listening to my Patti Smith and Can records while she cleaned house. I remember how desperately lonely it felt when she dropped me off for my first day of kindergarten; how she wrote me letters at Poste Restante in various European cities when I was bumming around; how she came to our apartment and read the entirety of Wilde’s Salome to my first girlfriend and me while we were still in bed. I remember sitting on her rocking chair with her when she read me the whole Lord of the Rings Trilogy at least three times through.

The funny thing about losing a parent, different from losing a friend, is that it is a loss of context. My mother was always there, the ground upon which my figure was defined, from the first moment of my consciousness until a few days ago. The loss is existential. For me, there were a few weeks during Mom’s dying when I felt that in some sense I was losing the audience for which I had been performing my whole life long. Even things Mom would never see, or never understand or appreciate if she did see, seemed somehow pointless without her.

To lose context, to lose purpose, is also of course to gain freedom. Owing to intricacies of my childhood, in a certain sense my one job in life has been to keep my mother alive, and, having finally failed, 56 years into it, there is an enormous amount of psychic and emotional energy available suddenly for other things. But it is a bitter freedom.

Mostly, now that a few days have passed, I am highly functional, but grief still descends on me, often when I am driving alone. At those moments I find myself sobbing again, strange cries pulled forth from my mouth, the cries of a child whose sole support and reason for being has been lost, phrases like “Mama, mama, this can’t be happening.” Sometimes I have to pull over and wait it out.

There is something pure and clear and overwhelming about this grief. When it comes on me I feel that every moment of despair in my life was in some way a facet of this loss, a tiny piece of it, was preparation for this tremendous unbearable sensation which I can’t even really name — it is a sorrow beyond sorrow, a frenzied sorrow, a boundless despair. Every heartbreak, every disappointment, every unrequited love, was only a foreshadowing of the vast sorrow and rudderlessness and refusal I am experiencing now. Perhaps even this is only a part of the yet bigger disappointment of my own death; we shall see.

Anyway, the memorial continued and I continued to weep. A few more poems were read and a few more people spoke to her and touched or kissed her. I spoke; I told my mother I forgave her for the difficulties of my childhood, realizing in that moment that, while objectively speaking did a terrible job (from a certain perspective), the ways that she was a terrible caregiver made me the man I became, and so by being a bad parent she was also somehow a good parent. I thanked her for undergoing pain I cannot even imagine, for visiting dark hell-realms no one should have to go to, on behalf of the rest of us.

I put on the mad music from Donnizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, which Mom adored, and we began wrapping her in her shroud, on which she had been lying these three days. Enshrouding a corpse is just like wrapping a burrito; I believe it is similar to swaddling an infant, with the important difference that the infant’s head is left exposed. You start by folding the shroud over the feet, then cross one side over the legs and tuck it under, then the other side, and work your way up. When we got towards her head I began to panic, and said to my wife that I didn’t think I could do this. Then I remembered that two younger friends of ours, who had known Mom well, had requested that we play her a song (The Crane Wife 3 by the Decemberists), and I wanted her to be able to hear it.

They had said they wanted to imagine the song swirling around her while she flew away into the sky like a crane. We used to call Mom the Egret Witch, which was how she seemed in her last years, her luminescent white hair flowing around her shoulders or gathered on top of her head. Another friend had had a similar vision while driving up to our place, seeing Mom in a cloud, one foot forward and taking off and dissipating into the sky.

Hearing the song reminded me again of how Mom had, on her own, learned to love some of the experimental rock records I listened to when I was a boy, and I saw, somehow for the first time, how her openmindedness, irreverence and independence had encouraged and produced my own; I told her this.

My wife sat on the side of Mom’s bed then, crying and talking and tucking things into her shroud. She tucked in three roses as requested by my uncle, a picture of my father, saying tearfully “this is for your sweetheart”. She tucked in a small letter embroidered with yarn, sent to Mom right before she died by a lesbian artist Mom had gotten close to in her last years, saying, “this is for your love and inspiration for young people, especially women”; tucked in some of those good almonds and a marshmallow, saying, “this is for your gusto for life and food”.

Then we were ready to enshroud her head. Like a burrito, you fold the shroud down over the head first, then finish by tucking the two sides of the shroud under. It was terrible to see her disappear, but astonishing the transformation that occurred. Just like that, the face we had all been gazing at, petting, and speaking to, gaunt, mouth open, dull eyes, was gone.

We all gathered around her busily then, wrapping six scarves tightly around her body to hold the shroud on and tucking flowers and peacock feathers in. She became more and more unearthly and beautiful as the process continued. Eventually we remembered the marshmallows and tucked them carefully into each of her scarves. Mom would have absolutely loved the humor of sending marshmallows into the crematorium to toast; she had a dark sense of humor, though she didn’t like being told so.

Finally, I took an old twig broom that was leaning near the door and tucked it into the scarf around Mom’s waist, saying, “I think she may need this”. She looked astonishing, mysterious, sacred and profound. The friend who was photographing decided to climb a ladder to get a view from above and while up there, she got a stony bemused gleeful look on her face and said, “I really suggest you all take a look from up here.” So we did, one by one, ascending the ladder and making a small bow, appearing to those on the ground as if Mom’s bed were a pool and Mom the reflection of someone about to ceremonially dive in.

As, indeed, is the case.

As we were taking turns standing on the ladder, the Rainbow Bridge Music from Wagner’s Das Rheingold came on — the music that depicts the gods leaving our world behind and entering Valhalla. Shortly after that the funeral home van arrived, the friendly staff apparently eager to get another look at our place. They bundled Mom onto their gurney, assuring us that everything would stay just as it was until Mom’s cremation; as they wheeled her out we struck the big bell three times.

The change in the emotional tone of the room as Mom was wrapped in her shroud was astonishing. We all went from paralyzed by inconceivable grief to joyously celebrating our dear departed friend. Though I’ve always liked the shift in tone at, say, a New Orleans funeral procession I really understood it then — the celebration is the continuation, the transcendence, the completion of the sorrow. Like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis, our joy at our own lives and happy appreciation of Mom’s life was only the natural result of all the weeping and despair at her loss.

༺ 𐂂 ༻

So, I hope these few words may encourage others to make their friends’ and parents’ deaths, even their own, an opportunity for practice and celebration in this way. When I first conceived the idea, I assumed it would be impossible, since we are not a recognized religious institution, and it took a while to find anyone who could tell me anything about what would be required. As it turns out, the laws governing dead bodies are pretty vague and a lot is up to individuals: To funeral directors, care home staff, van drivers, families. Some funeral parlors will allow you to transport a body in your own vehicle; they do not advertise this on their websites! Some funeral parlors, on the contrary, insist on visiting you in your home to sign a paper contract before death and make it difficult to avoid an expensive casket.

The death doulas we worked with were wonderful, but honestly not much help in navigating these strange and tangled microbureaucracies. I had to call and email, sometimes repeatedly. Luckily my wife and I had grown adept at doing this in advocating for Mom with the ridiculously, criminally inefficient bureaucracy that is health care in America, particular for the elderly. But I think for me the moral is that death is such a taboo subject in America that our practices around it are unclear; there are a limited number of things that people do, simply because they do not know what to do, have never thought about it, have been encouraged not to think about it, by their religious and most of all medical professionals — and a variety of unscrupulous entrepreneurs take advantage of this.

When my aunt died, in hospital, the hospital asked me which funeral home we were using and when I said I didn’t know, they looked dismayed and said, “Well the body can’t stay here.” My aunt had been told by doctors that she might “beat her cancer”; they kept telling her that until her hospital-caught pneumonia got to a stage where the nurses were giving her enough morphine that she never had an opportunity to realize she was dying — with the result that she and I had never had a conversation about her wishes after death.

I vaguely remembered that she had told me something about being a member of the Neptune Society, which I understood was an organization which you prepay for eventual cremation and scattering of your ashes at sea; when I told this to the nurses they looked at me blankly. I googled and found a phone number, called the Neptune Society and asked them what to do; a sleepy-sounding person checked their records and could find no record of my aunt. Eventually they agreed to come and pick her body up anyway, as the hospital was becoming agitated.

A day or two later I got a call from the Neptune Society, confirming that they did not in fact have any record of my aunt being a member, though they did have her body. When I said I was sure she had been, they asked, “Has she lived anywhere else? This is the Neptune Society of Oakland, might she have been registered with another Neptune Society?” I said, “Are there more than one?” “Oh yes,” they told me, “there are hundreds. All independent private companies.” Shocked, I asked, “Well if she was registered with one of the many other Neptune Societies, what do we do?” “Well, you can pay us for cremation — it’s $1600” they said.

Finally I found someone who agreed to check with some of the other local Neptune Societies to see if my aunt was registered with them and, as luck would have it, they found the correct Neptune Society rather quickly. There was some haggling over the body, as I recall, because, of course, the wrong Neptune Society had transported and stored the body, normally a rather expensive procedure, but they sorted that out among themselves (I suspect this situation must not have been all that uncommon), and eventually we were handed over some ashes which were allegedly my aunt’s. I now know that, in addition to all the Neptune Societies, there are innumerable Nautilus Societies, Poseidon Societies, and who knows what all else — all of whose business models are based on confused elders, bereaved survivors, and a general inability to openly discuss the matter of death.

༺ 𐂂 ༻

Clean dead bodies are not dangerous or disgusting, not in the days immediately after death. They are, however, very eerie. It is the confrontation with this eeriness — as much as the opportunity to grieve viscerally, and in your own way, on your own time — that is so profound about spending time with the dead. I am convinced that there is a deep and precious teaching in it; that this is a gift we can give each other by dying, a teaching we can offer, merely by being as we are, our whole selves, our simple inert selves, after we die.

It would be a crime to limit this teaching by putting it into words, but I will say that one facet of it is appreciation of life and of the living community of comrades and beloveds with which we are blessed; I am methodically contemplating each of you as I write this. Be well, stay free, and don’t give up.

2022, Early Spring, 3º Lunation, Waning Gibbous Moon

Turtle Island, California, Nisenan Rancheria, San Juan Ridge, Moonflower Mahasangha

Touch Fucking Moonflower